Enhance!

If AI is making everything better, why is everything getting worse?

Adobe has been having a rough go of it lately.

First there was the understandable outrage from photographers when the software maker began promoting new AI-powered features by enticing users to “skip the photo shoot.” Then the company sparked an outcry when it updated its terms of service requiring commercial photographers to agree to terms that would violate client contracts and (seemingly) allow customer images to be used for training its Firefly AI.

And finally, just this week, Adobe was sued—and it’s a doozy. Not just any old lawsuit, this one was brought by the U.S. Department of Justice on behalf of the Federal Trade Commission, which accuses Adobe of deceptive business practices. This has led to higher than usual levels of schadenfreude, though I can’t say the company hasn’t earned it.

The DOJ alleges that Adobe’s practice of defaulting customers to its most lucrative monthly subscription without properly disclosing its annual term and hefty early termination fee is illegal. Further, the suit alleges, “When consumers reach out to Adobe’s customer service to cancel, they encounter resistance and delay from Adobe representatives. Consumers also experience other obstacles, such as dropped calls and chats, and multiple transfers. Some consumers who thought they had successfully canceled their subscription reported that the company continued to charge them until discovering the charges on their credit card statements.”

If that isn’t emblematic of the state of customer service in 2024 I don’t know what is. As a bit of a consumer advocate myself, I’m always glad to see any predatory megacorporation get called on the carpet by the U.S. government. Checks and balances and all that.

What will it mean for Photoshop users? Unfortunately, my cynical guess is not much.1

If this doesn’t make you want to put your head in the oven, kudos for being stronger than me. I’ll be curious to see if Adobe changes tactics in any meaningful way, but I’m not betting on it. Their approach is, by the only measure that matters, an unmitigated success. The company continues to post record profits and recently celebrated its third consecutive $5 billion quarter. Analysts attribute Adobe’s financial success to the growing inclusion of AI-powered features in its products.

So maybe they and other tech companies will start behaving ethically just because it’s the right thing to do.

I asked Google “What is Adobe?” and, contrary to recent trends, it provided a useful result: a brief explanation that adobe is a building material about which I could learn more with a click, while acknowledging that I was most likely looking for the $233 billion software company of the same name.2

The description that Google displays is provided by Adobe.com, and I find it fascinating: “Adobe is making the world more creative, productive, and personalized with artificial intelligence as a co-pilot that amplifies human ingenuity.”

It’s not the use of the Oxford comma that’s got my knickers in a twist, it’s the omission of an actual explanation of what the company does in a meaningful way. No mention of design, photography or video editing, or any of the 50-something applications the company develops. Instead it’s just facile marketingspeak about AI as a tool for creativity.

I recognize that my skepticism is thinly veiled. It’s not that I’m above believing that AI can and does provide benefits—particularly when it comes to handling mundane tasks that, at least theoretically, free us to have more time for the fun stuff. It’s just that with every passing day, with every new PR buzzword, I believe less and less in the prospect of a meaningfully useful AI future. As Ryan Broderick puts it, the current state of AI is “not totally dissimilar from what happened during the cryptocurrency bubble during the height of the pandemic: Hundreds of startups, flush with cash from a bull market, started trying to build crypto-backed consumer products after they had already decided the technology was the future—not the other way around.”

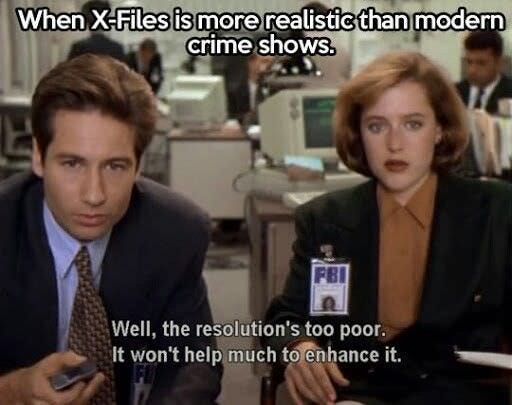

You know when you’re watching a CBS crime drama and the brooding investigator is standing over the shoulder of the computer whiz and there’s some picture of the bad guy caught in the act, but they can’t quite make it out? What happens next, typically, is the whiz kid clicks away at the keyboard and mutters something along the lines of, “Enhance!” The formerly low-resolution image does a pixelated dissolve revealing… Dun dun duuun... the bad guy’s crystal clear evildoing face.

As anyone who has ever opened Photoshop knows, “Enhance” is not a thing. And that, I contend, is evidence of what I’m going to call the single greatest challenge that’s shaped the camera industrial complex for decades: resolution.

First, in the film era, there were consumer cameras with 35mm frames (or smaller) that provided perfectly nice prints so long as you didn’t go too big. If you did want bigger prints you moved to medium format or a 4x5 view camera for much more information—or even an 8x10 camera for exponentially more detail. Bigger, in film then as it is with digital now, is better.

I once shot something for a client on 4x5 with the intention of blowing it up to a 6x9-foot backlit transparency in a trade show display. When I finally saw the thing up close, printed taller than me, I put my nose to it and marveled at the detail. Far off in the background I saw things I didn’t know were in the negative—a construction crew at work several blocks away, for instance, and legible traffic signs far off in the distance. That big negative contained a whole world of detail that was captured but could not be seen until it was massively enlarged.

When we moved into the digital era, I had that enlargement in mind as I thought about what it would take to replace film. I recall being taught that digital cameras wouldn’t take over for 35mm film until digital sensors reached 9 megapixels. So I suffered through 3 megapixels and then 6 megapixels, until finally my Canon 5D delivered 12 megapixels of glorious detail. We had arrived.

Now, as I’m sure you’ve noticed, manufacturers keep introducing higher and higher pixel counts: 20 megapixels became 40, 40 gave way to 60, 60 set the stage for 100. There are certainly wonderful uses for a 100-megapixel digital sensor, but I do find it ironic that in an age in which print is dead and most commercial photography is displayed on phone screens, we’re still being sold on the idea that we should continue shelling out a small fortune to stay up to date on the latest camera tech.

Which brings me back to “Enhance.”

Camera makers worry a lot about pixels, continuously striving to make bigger, better, sharper images without making cameras prohibitively expensive for the shrinking audience that still wants a camera and a smartphone. People pay good money to get bigger, better, sharper images. Because the only way to do that is by starting with a bigger, better, sharper sensor. Because in the real world, “Enhance” is not a thing.

Unless…

What if generative AI is the “Enhance” button for the next stage of imagemaking?

AI has already demonstrated the ability to upgrade the perceived quality of an existing image through interpolation, contrast and sharpening tricks that allow a file to be upscaled without a significant loss of quality. Could “Enhance” finally become real? Could we present an image to the AI and ask it to fill in the details—revealing the construction workers blocks away in the background, or the road signs far off in the distance, or the detailed face of that evildoer caught in the act?

Not really. It still doesn’t work that way.

The whole reason photographers fork over vast sums of money to a handful of camera and lens manufacturers is because, no matter how amazing Photoshop and other digital tools have become, the one thing they cannot do, the thing that has been perpetually unattainable, is “Enhance.” This is because of a principle that remains absolutely unbeaten: garbage in, garbage out. The quality of the information coming out can never be better than the quality of the information that went in.

Whatever we’re doing—digital imaging, audio recording, whatever—we’ve got to start with the highest quality input, because every subsequent iteration degrades quality. Sometimes it’s barely noticeable, or even all but inconsequential, but it’s there. Make a copy of a copy of a copy and keep repeating and see how long it takes before the result is exponentially inferior to the original. We must start with the highest quality input because it’s all downhill from there.

It strikes me that this is how generative AI works too. It’s a copy machine, not a create machine.

Yes, AI can “make” an image by examining other images and outputting a mashup based on what it’s taken in, but can this new image ever be better than the original? I don’t think so. Because it’s just a copy of a copy of a copy.

AI image generation does not start from scratch, it starts with a vast database of existing images. What it understands of the world is defined solely by images that already exist, by virtue of having been photographed or drawn or painted by humans. No human-made images, no generative AI.

AI, at its essence, is designed to be derivative.3

Imagine a world in which AI has won. And now, since AI-generated photorealistic illustrations have replaced photography, every new iteration is a copy of a copy. Soon enough, every new AI image is based on a previous AI image. With every iteration it gets further from any recognizable reality. Send the image through the copy machine enough times and humans in pictures will have six fingers, bad teeth and demon eyes.

If generative AI succeeds, that success will ultimately lead to its downfall. Without reality to copy, the input becomes contaminated. Garbage in, garbage out.

Lest all of this come off as anti AI, allow me to explain that I think of myself simply as healthily skeptical of big tech companies promising the world so long as I give them my credit card. It’s good for business, sure. But is it good for actually helping humans do the things we do best?

Interesting and useful, fine. But when it comes to the things that deeply matter, to enhancing our creativity and ingenuity? When it comes to making the next Mona Lisa? I’m calling it now: no way.

Just today I received an email from a company that had been successfully sued, apparently on my behalf, and so I was refunded a whopping $9.72 because, after I spent hundreds to thousands of dollars with this company, they disclosed (i.e. sold to the highest bidder) my personal information and medical history. I’ll try not to spend it all in one place.

A cynic might point out that Google here is simply being capitalistically prudent. It stands to profit from sending searchers to the software giant’s website, as the mud-as-building-material gang isn’t likely to be working with quite as big of a marketing budget.

Unless we achieve artificial general intelligence, the holy grail of AI, which scientists remain undecided about whether or not it can actually happen. They do seem to agree, though, that if it does happen it’s going to destroy the world. Which I think would mean I’m technically still right.

I briefly quit using Adobe in 2020 because even with a high spec laptop, PP crashed constantly. Going more than 15 to 30 seconds without hitting ctrl s was a recipe for frustration (it felt like using a buggy beta program). So I looked for alternatives and found them in Capture One and Davinci Resolve. Capture One actually worked better with Nikon raw files than LR and why anyone uses anything but Resolve for video editing post 2020, I don't understand. But I only made it about six months before missing things (and layers) that I can only get from PS. And that's how they got me. I still hate the subscription model with a passion though, so I'm happy to see any wrist slapping they can get for strictly schadenfreude reasons.

The Adobe terms and conditions update was the final straw for me. After an almost thirty-year business relationship with that company, I canceled my $60/month Creative Cloud subscription. I have replaced them with the Affinity Suite by a company called Serif. The learning curve is surprisingly easy, and I pay them a fraction of what I pay Adobe.