You should’ve seen the lede I initially wrote for this story. Building on the headline, it was Shakespearean and ridiculous.1 Ultimately, though, I scrapped it in favor of cutting straight to the point: is it better to specialize as a photographer, or is it better to be a generalist? I know the answer and I will share it with you. But much like an online recipe writer, I’m gonna make you work for it.

I have been spending time on Threads lately and I am pleased to report that the algorithm is steering me to a community of photographers who are mostly friendly and helpful. Mostly.

Some folks are a bit preachy and whiny and reminiscent of the petulant attitudes prevalent over at The Place Which Shall Not Be Named (as well as the insufferable Business Place About Which Nobody Cares) but for the most part I’ve experienced a positive, helpful community vibe. Hopefully that continues.2

One recurring topic of discussion there is about specialization. Should a photographer focus their attention on one particular discipline, one specific subject, one single style of photography? The consensus is clear: no.

I’m seeing growing disdain for specialization. The staunchest generalists deem it necessary in our brave new post-everything world to ravenously pursue anything and everything. Niches are passé, they say. Now it’s the voracious haver of diverse photographic experiences that is destined to reign supreme.

I disagree with this sentiment. It flies in the face of what I have been taught by numerous photographers considerably more successful than I, as well as my own personal experience. But before you compose a sternly worded letter, allow me to explain.

Over the course of 20 years of magazine writing I’ve been fortunate to interview hundreds of great photographers, the vast majority of whom specialized, and many of whom cited specialization as key to their success.

For instance, when I spoke to photographer Vincent J. Musi for a 2017 profile, he told me of attending a gathering with his National Geographic colleagues, lamenting how the days of generalization were over.

“Everybody in that room has a specialty of some kind or another,” he said. “Mine always was kind of general assignment, but I’ve moved into doing animal stuff. You’ve got underwater guys, deep underwater guys, people who only do bugs, people who do landscape only… If there’s a change in the wind there and they decide they don’t do landscape anymore, or they decide bugs aren’t cool, you can spend some cold years not having any work.”

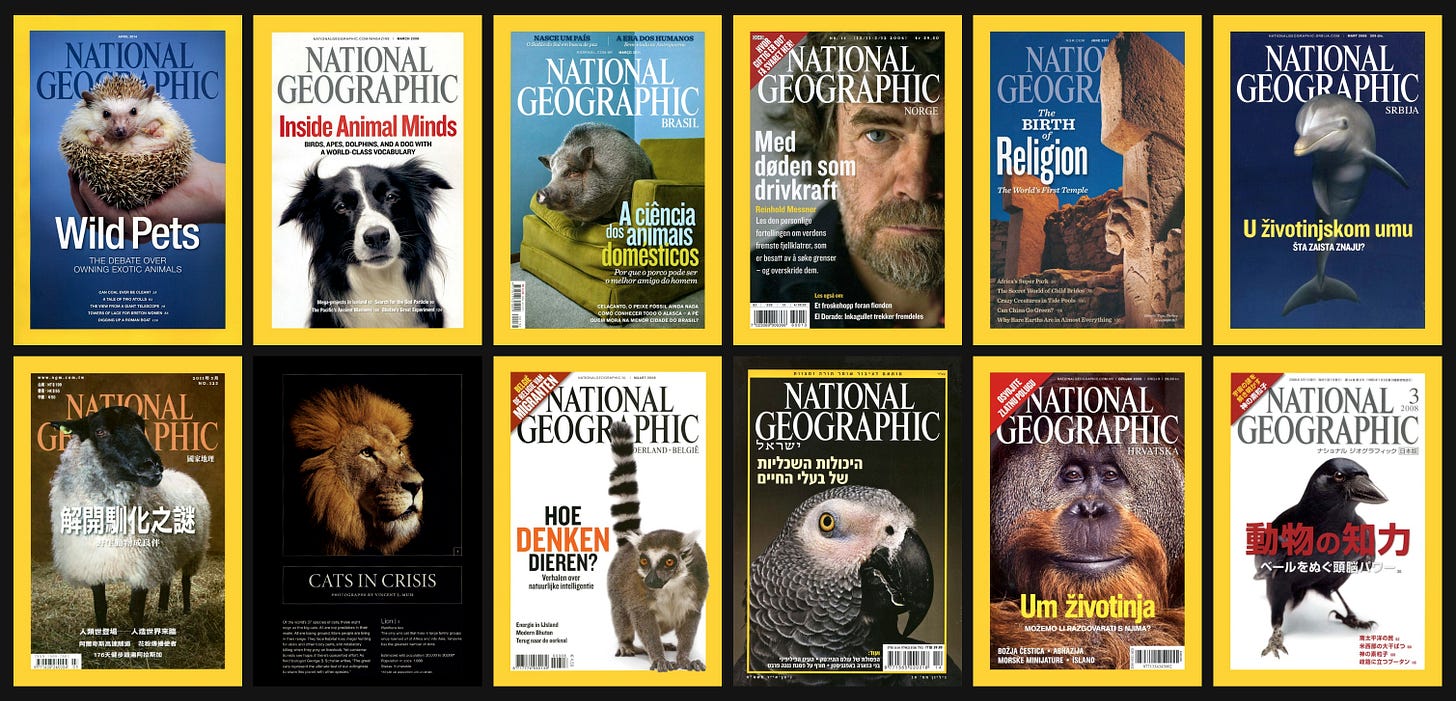

That succinct comment lays out two primary pros and cons of specialization: discerning customers demand expertise (as evidenced by Musi’s raft of NatGeo animal covers, below), but if the thing you do falls out of favor, both your brand and your bottom line take a hit.

Almost without fail, photographers who sell their work—be it assignments, stock, or fine art—have long reported to me that specialization is instrumental in their success. Mr. Musi was, after all, being profiled in that magazine precisely because of his expertise in one specific niche.

When I spoke to Jeff Brenner a few months ago for this very publication, he echoed the same sentiment. It’s the credibility of being an expert wildlife photographer, and the brand that built, which allows him to earn a living selling prints.

Another story always rings in my ears when the topic of specialization comes up. In an interview with still life photographer extraordinaire Jody Dole way back at the beginning of my career, he laid out the importance of specialization. Bear in mind that Jody has an amazing portfolio that should make it clear to anyone with half an eye that he is as good as it gets when it comes to tabletop photography. It is, in fact, his specialty. Still, that’s sometimes not enough to land a gig for which he’d be perfect.

“Clients want to see exactly their shot in your portfolio before they’ll hire you,” he said. “I have this great shot of a pretzel, and I was up for a potato chip job. ‘We know you can photograph a pretzel,’ they said, ‘but can you do a potato chip?’ The client hired the guy with 15 mediocre potato chip pictures rather than making the leap of faith with the guy who had the great pretzel shot. My favorite line, when I hear this from clients, is ‘You remind me of Pope Julius.’ It’s like, ‘Yeah Michelangelo, I know you can do a chapel ceiling, but we have a synagogue.’ So yeah, I can paint a synagogue.”

Dissenters, I’d guess right about now you’re thinking that these stories represent a different time in photography, a pre-pandemic era of big budgets and clients who cared about quality. Not to mention a time before A.I. You are not wrong. But the changes that are already happening to photography, and which are sure to snowball into the future, are precisely why specialization will become more important, not less.

Think about it in relation to any other industry. Who do you hire when you want something done right? When you need a new roof, you call a roofer. You don’t know which roofer, but from the jump you know it’s not going to be a handyman or a carpenter, you’re going to hire a specialist in exactly what you need unless budget constraints force you to choose a generalist who can likely get the job done well enough at a lower price. When we want something done right, and we are willing to pay for it, we seek out a specialist.

The generalist photographer is like the handyman. These folks are great resources to have at your disposal, and they generally do a pretty good job at a wide variety of things. But a jack of all trades is unlikely to garner the most interesting, challenging, high profile and well paying jobs. Generalists rarely reap the rewards of deep expertise. They are instead called in when there’s no time, energy, or budget to hire an expert. Does this sound like a recipe for longterm success?

Specialists are fishing in a smaller pond, for sure. But they are positioning themselves in a place of strength when it comes to pricing and negotiating because they have an expertise that is, at least to some degree, rare. Scarcity is why specialists garner higher rates.3 And it’s why specialists are up for consideration for every job within their purview. I’ve been both a generalist and a specialist, and let me tell you: the better jobs, with better pay, and a better sense of satisfaction all stem from specialization.

Marketing yourself as a jack of all trades sends the message to clients with high standards and budgets to match that you are a master of none.

Counterpoint, Sorta

Note that the entirety of my argument in favor of specialization is a business case. When it comes to leading an interesting life, having fun, and enjoying your photography as anything other than a method to feed your family, yes, by all means, generalization is the way to go.

It makes sense too, of course, because that path is going to be vastly more interesting. As photographer Jay Maisel famously said, if you want to make more interesting pictures, first become a more interesting person.

This point was made well by

in his Substack post earlier this week. At first glance it seems to fly in the face of everything I’m writing here, but I think Don and I are actually making the same point from different directions. Don is writing about being a more well rounded, more interesting and more interested person by pursuing a diverse set of subjects. And with that, I wholeheartedly agree. It makes for better people, better employees, and maybe even better artists. But when it comes to a working photographer’s portfolio, when it comes to marketing, branding and pricing, generalists have a harder time.Mixing landscapes with wildlife or street photography with portraiture, this is the most interesting and exciting approach to photography, for sure. Because it is fundamentally without limits. That thing you’ve never shot before, which you might shoot tomorrow, could be the most fulfilling photograph you’ll ever make. And the only way to find out is to keep searching, keep growing, keep trying new things by exploring every avenue of photography (and life) you can get your arms around.

If your goal is to enjoy photography, to explore the world with a camera in hand, to make images for your own creative edification… Then yes, by all means, shoot anything and everything you want. It’s interesting, fulfilling, and certainly an opportunity for exploration. You have my blessing.

But my advice is very different for photographers aiming to earn their living with a camera. Or more to the point, for those trying to get past surviving and move on up to thriving. The road to success starts with a specialty.4

I began my career as a generalist commercial photographer. I shot products and architecture and portraits and events and almost anything else that crossed my path. But after hearing directly from all these magazine-cover photographers time and again about the importance of specialization, and thinking about Jody Dole’s potato chip, I began to focus my portfolio and my marketing efforts on one specific niche: corporate portraiture. My rates climbed, my capabilities improved, and I know I have a shot at getting any pertinent job that crosses my desk. It’s an empowering feeling, if I’m honest. And this is a career in which—or at least I’m a photographer for whom—opportunities for empowerment are few and far between.

Here’s the secret that one of those super-successful photographers shared with me when I divulged my own years-long struggle with whether or not to specialize: You still keep shooting anything and everything you like, but you only market one thing. That’s your niche.

Hallelujah! Why didn’t somebody tell me this sooner? Specialization is a marketing strategy. Shooting everything under the sun is good for paying the bills and staying creative and interested/ing. You need not decline work outside of your niche, but by marketing a more focused specialty your rates will rise and your calendar will fill. You will become a sought-after expert.

That is why I, a corporate specialist, have in the last couple of months shot tabletop product photography for an aerospace manufacturer, architectural interiors for a contractor, and models donning baseball caps for a hat catalog.

We market only our niche, but we do whatever we want. We contain multitudes.

The Fine Print

There is a time when a photographer should actively avoid specialization, and that is when they are learning. It is important to try all sorts of things and see what sticks. I had zero interest in portraiture when I emerged from photo school, but as my generalist gig included it, I took a liking to it and discovered not only a knack but also that I could make a business case as well. Perhaps most importantly, I really enjoyed it. And I would never have found my niche if I didn’t try a whole lot of different things when I was starting out.

There’s also a more insidious downside to specialization, which accompanies even a modicum of success. When you find something that works it gets harder to do anything else. Much as a sitcom actor may bristle at being typecast, a specialist photographer may find the grass seems greener over in the generalist’s yard. After 20+ years as a commercial photographer, I know first hand that the narrower your specialty, the greater the risk of burnout. You have to actively fight against going through the motions, relying on the tried and true, and the entirely anti-creative feeling of having an assignment figured out before it even starts. This is especially painful if, like me, one of your favorite photographic activities is exploring the world with a camera in hand.

I fight stagnation, this tendency toward burnout, by finding work that brings me joy—both outside my niche and via technical and creative exploration within it.

A new argument in favor of generalization is that what worked ten years ago isn’t working as well today and won’t work at all tomorrow. This seems plausible enough, especially as photography takes a backseat to video and an uncertain future full of AI. But these threats to our work will consume from the fringes, first and foremost. I ask you, will AI replace the nuanced, specialized work at the top of the market? Or is it more likely to erase value and opportunity at the bottom of the ladder, where handyman photographers are stuck churning out content?

I do believe it’s essential for aspiring photographers to have a broad range of skills they can pair with photography (such as video, for instance, or writing, or graphic design). But this is aimed at making one more employable, a more desirable colleague and team player. In a world where everybody I know is doing the work of two or more former colleagues, being a “photographer and” seems like a real advantage when it comes to finding a job.

If you’re trying to become the next Avedon, Adams, Arbus or Annie, though, you’re gonna need a specialty.

I fundamentally believe that to rise above, to have a shot at greatness, or just to set yourself apart from the unwashed masses, meaningful success requires specialization. Use those other skills to get your foot in the door, to pay the bills, to keep yourself sane. But to rise through the ranks you need a niche. It’s the approach I’ve been taking, so if I’m wrong at least we’re in this together and if I fail you can always point and laugh.

No matter what may change in our culture, our media, and in the value of photography in general, what doesn’t change is the law of supply and demand. There are an awful lot of generalists out there, and the generalists have a supply problem. We specialists have a demand advantage. Not everyone needs what you sell, but those who do are willing to pay for it.

Start a photography career by experimenting with many different things, see what moves you. It’s okay that you don’t specialize, until it becomes essential that you do.

“Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of a photographic life in pursuit of anything and everything, of that which presents itself willy and/or nilly to the artist’s wandering eye… Or, perhaps, at such time as we are ready to shuffle off this mortal coil, we will look back and say ‘Dangit, I should have specialized in one particular photographic niche.’ That is the question.”

And, while we’re at it, why photography prices have stagnated or declined since the digital revolution as more and more “experts” have entered the fray, supply and demand dictates our expertise is no longer as rare as it once was.

Interestingly, once you achieve unmitigated success, you’re free to start generalizing again, following your whims and interests wherever they may lead. See André 3000’s new album of flute music. Or Michael Jordan switching to baseball. Or any number of wrestlers, athletes and singers who have moved into acting, politics and myriad other pursuits.

When I hear the debate over generalist and specialist, I'm reminded of "Specialization is for insects," Robert A. Heinlein famously wrote. "A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly."

I cannot intelligently comment on your take concerning marketing your specialization. I'm not attempting to market my photography. The joy of retirement means doing what you want, when you want.

Yes, a great read! And I am printing it out to read more than once and to mark and learn from the tips. And now for a bit of my own "specialization story" and it has "phases". First I was in art schools for about 5 years while in junior high and high school and had art classes also in high school. Never once took any formal photography lessons but concentrated on painting of all kinds, sculpture, charcoal/conte crayon and silver point and making sterling silver jewelry. Went on & off to the Cleveland Institute of Art. Wandered in and out of the Arts Students League in NY where I did nudes from live models. Applied to art schools for college and got into RISD, Tyler School, and Kent State as an art major because I decided to stay closer to home. Loved the classes, but the riots happened there on May 3rd with tanks showing up and then on May 4th the National Guard with bayonets started shooting people.

Depressed and with PTSD, I decided I could not figure out how to make a living as an artist, so never took an art class again.

I did get 2 presents in 1970: A used Zeiss Ikon and used Rolleiflex Twins Lens Reflex. Started taking pics and developing them myself just for fun while I worked on a Bachelors to become a law librarian, got a Masters in Law Librarianship and Information Science with a concentration in database work for legal research. Got a law degree and am approaching 50 years as a lawyer that concentrated primarily on workers compensation defense /risk management in a private firm and later as an Assistant County Attorney. I've represented big time insurance companies, McDonalds, Eastern Airlines, hospitals, trade associations, cities, Miami-Dade County and all of their various departments, including police, fire, seaport, airport. (There was an entire group of lawyers in that municipal law firm--one of the largest in the country-- all working the same kinds of cases and no lawyer in the office was a generalist.)

Along the way while making a living as a lawyer I got into dress design such as my wedding dress, and home fashions, such as drapes, bed spreads and shower curtains. I sold nothing: all was a hobby.

AND THEN: My "specialization" radically changed. In 2010 through present I've never looked back at my old cameras and never used any non- digital camera again. I got the first of 7 iPads and 2 iphones and several Android phones and tablets, and they are my ONLY cameras. I have now amassed more than 5,000 images that are halfway decent, more that are crap, and have been working on 2,500 to sell. I have many Smug Mug galleries behind the scenes -- meaning not live yet--with "general commercial" photos and products to sell and am seeking out other sites for other products such as silk scarves, table linens, upholstery, decorative pillows, wallpaper, fabric for dressmaking , drapes, bed spreads, table linens, and wrapped furniture all based on my photos. I am also planning large scale 8' x10' photos for entry into shows such as "Art Basel" and I'm researching who can print those wall size photos for me.

So what kinds of pics? Anything and everything: from portraits, to street photos, to landscapes and cityscapes, to elaborately designed collages incorporating "things", such as my clothes, jewelry, kitchen items, family heirlooms, dogs, all manner of "home wildlife", including roaches, mice, lizards, rats, iguanas; my old art work, kaleidoscopic and fractal pics, still lifes, wrapped boxes, and jigsaw puzzles up to 10,000 pieces, political and other cartoons, and graphic stories. I submitted one political cartoon about Putin and his "chef" to the New Yorker, but was politely declined.

I certainly can't die: too much to do. But like "Grandma Moses" from the 50's and 60's, there are quite a number of working artists in their 60's to 90's all around the world and the ones I am talking about happen to be female. So I look forward to being actively involved with fellow photographers and artists, lawyers, political junkies, writers, poets, other creatives, Everyone! on Substack. I'll be starting a newsletter here sometime within the next six months, and of course I'll illustrate with my work of all kinds.

(And incidentally, there happen to be many creative lawyers-- whether writing fiction, poetry, crime stories that also get made into movies presently and back through history as I'll write about in my newsletter. Even the ABA-- American Bar Association gets involved: they have competitions among lawyer-artists, a yearly "Peeps" Diorama competition, and write up's and publicity for lawyers that write fiction, and of course, there's the career specialty of "courtroom art" where the artist might not necessarily be a lawyer, and there are the artists, sculptors, and photographers that reconstruct faces backwards and project forward when such is needed in a criminal law case. And incidentally, the super-computers that can solve jigsaw puzzles can also solve forensic work as putting together shattered ceramics that have become evidence in a case, and bones in an anthropological or criminal investigation.) investigation.