This is the second installment in a three-part series about America’s changing relationship with permission as it relates to photography. You can read the first part here. I am not a lawyer; this is not legal advice. Rules in the U.S. are not rules everywhere else. Don’t get thrown in a Turkish prison.

Sometimes I go outside. And sometimes—believe it or not—I take my camera. Controversial? Somehow, yes.

Taking pictures in public is my right as an American. I can point my camera at almost anything I want. I can’t use it like a peeping Tom, and I can’t trespass in the process, but other than that, generally speaking, when I am on public property there is practically nothing illegal I can do with my camera.1

I can photograph strangers, I can photograph women, I can photograph kids, I can photograph pets, I can photograph buildings, I can photograph police, I can photograph politicians, I can photograph birds, I can photograph advertisements, I can photograph trains, I can photograph fancy private brownstone residences with old brass plaques by the door, I can photograph cars, I can photograph photographs of photographers photographing. If it exists in public I can look at it as goddam much as I want to, even if I’m looking through a camera.

One thing I can’t do is use my camera to peep into a neighbor’s window, or in any other area where a reasonable person would assume they have privacy. We have the right to not be photographed when we are in private. Such invasive use of a camera is in no way protected. And that is as it should be.2

But no reasonable person should assume they have the right to privacy in public. How could you? Have you seen public? There are so many people there.

There’s no right to privacy in public. This holds true in sidewalk cafes, in city parks, on small town streets, at crowded beaches, and in any and every other public space. I am free to point my camera at any and all of those things in any and all of those places. It’s fairly safe to assume if I can see it I’m permitted to photograph it.3

Don’t hear what I’m not saying. Just because I can point a camera at you in public does not mean I am free to do whatever I want with that picture. Usage matters. I can’t license your image for an advertisement, for instance, because each of us have the right to control our likeness for commercial purposes.

But “commercial purposes” does not include editorial use. So if a newspaper photographer is covering a story on, say, people in the park enjoying lovely autumn weather, he is not only free to photograph you in the park enjoying lovely autumn weather, but to also run it on the front page of the newspaper where a million people will see it. He doesn’t have to ask you, or pay you. He doesn’t even have to say thank you.

We Americans have an exceptionally limited ability to control who can take our picture in public. And that, too, is as it should be.

The conventional wisdom, however, is changing. Out in the world as well as on social media, people are implying with increasing frequency that this topic is up for debate. It isn’t. The premise put forth is “You need to ask permission before taking someone’s picture,” which is simply not true. You don’t need permission. It’s a fundamental freedom protected by the First Amendment.4

The Washington Post uses the slogan “Democracy dies in darkness.” This stuff is kinda what they’re talking about. Oppression and corruption thrive when we aren’t free to tell the truth, to pull it out into the light and photograph it for all to see.

If your presence is lawful, your camera is too. Say it with me: Photography is not a crime.

Yet street photographers are getting beaten up, photographers are being reported to police, and a whole new genre of YouTubers has sprung up to fight for our right to take pictures in public.5 As public surveillance increases and facial recognition software becomes more ubiquitous, my guess is this trend is only going to get worse.

If you tuned in last week, you read stories of times I got stopped by government officials and corporate security guards who wanted to know why I was pointing my camera where I was. While I haven’t had many run-ins with individuals getting mad that my camera is aimed in their direction, I am very cognizant of the fact that (some) people are on edge about having their picture taken even when they’re in public. It seems to me that things are getting worse in this regard. It’s a feature of modern life that, I would posit, is thanks largely to social media. Since cameras have become ubiquitous and knowledge (information, proof, facts) is power, cameras do more damage than ever. In the information age, you might even say they’re weapons. Ipso facto, photographers are dangerous. Just not in the way the government suspected.

We are now so sensitized to the ways in which images travel the world at lightning speed, making infamous the likes of Hawk Tuah Girl, Side-Eye Chloe and Scumbag Steve, that we have become especially protective of being photographed in any way that might lead to our becoming the next viral sensation, with all the embarrassing fame (and lack of fortune) that accompanies it.

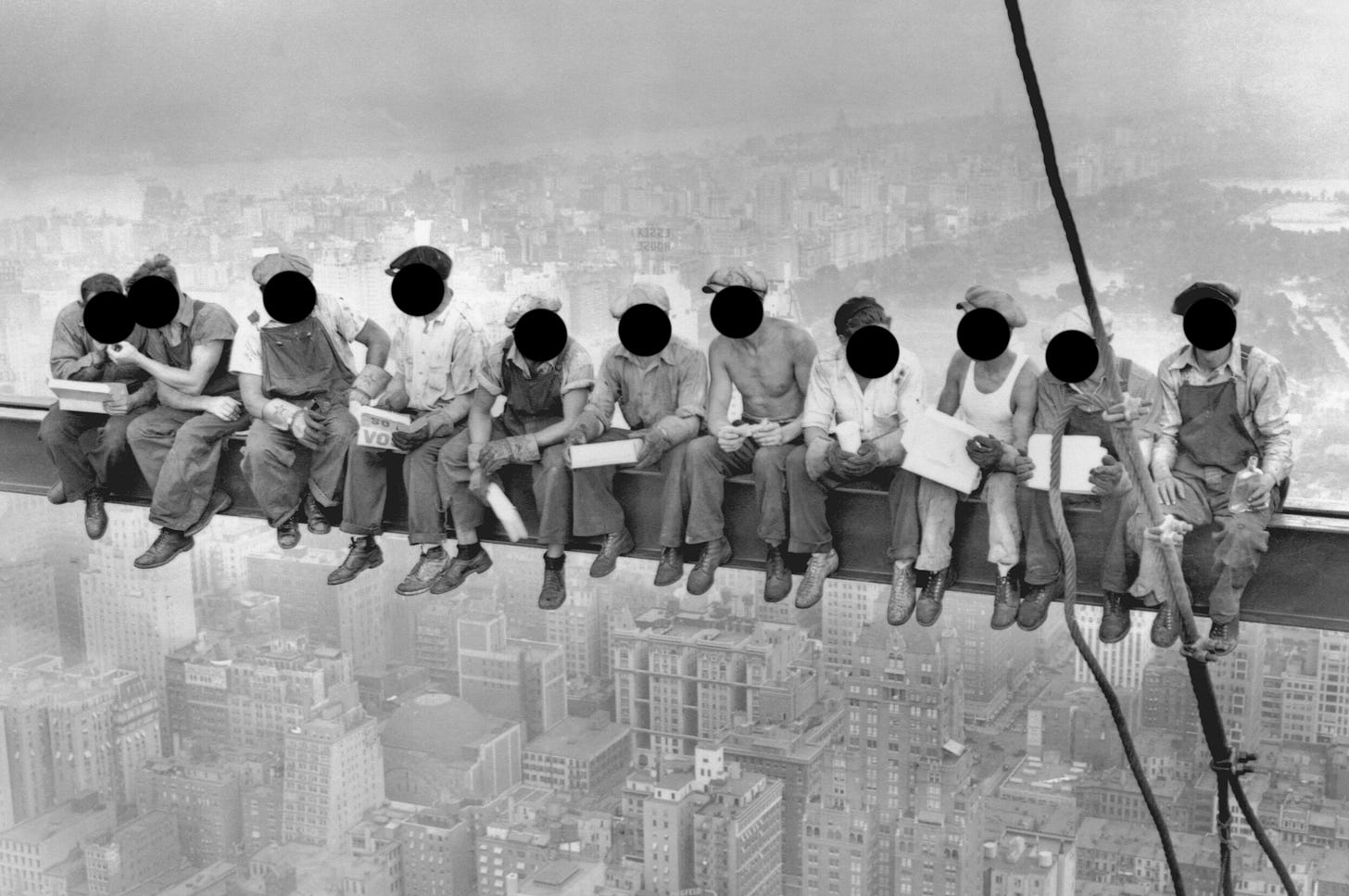

I sympathize with the concern, minimal though it may be. But clamping down on photography will not solve the problem. In fact it would create more. Forget issues of press freedom and the fourth estate’s system of checks and balances. From a quality of life standpoint we’d lose so much. Imagine your favorite 20th century photograph. Maybe it’s Cartier-Bresson’s puddle jumper, or Steiglitz’s Steerage, or Ebbets’s Lunch Atop a Skyscraper. If it’s got a person in it, and if those people didn’t give permission, delete that image from history.

“But Bill,” you’re saying. “We don’t mean you need a contract, we just mean you should ask somebody ‘Hey, can I take your picture?’ Is that so difficult?”6

I get the idea, but what do you think is the consequence of even the tacit requirement of permission? It implies that without it, the act of photographing a stranger is somehow rude, manipulative, aggressive. That’s not a good precedent. This would lead to conflict, and preventing conflict is going to require proof. In other words, paperwork. A signed contract.

Forget the law for a moment. Even just a change to the status quo, to the conventional wisdom, would be more than enough to damage photography’s cultural relevance. Because even if it isn’t actual law, the vigilante enforcement of a commonly accepted practice might as well make it so. We’re already seeing that idea play out again and again.

Sure, there are lots of occasions when “Hey, can I take your picture?” is the reasonable, decent thing to do. I do it all the time. But there are also situations in which it is not. And, again, that is as it should be.

There is no right to privacy in public, and we need to stop pretending there should be. If you don’t want my camera to see you out in the world, my eyes shouldn’t be able to see you either. The onus is on the one seeking privacy to avoid the public space. It’s not unreasonable to not want to be seen. That’s why some people stay home.

Why am I ranting about all this? Because I keep encountering reasonable seeming, well-meaning people on the other side of the argument being taken seriously. There’s nothing to be gained from preventing photography in public spaces, and that’s exactly what a “right for permission to photograph” would accomplish. Brandishing a camera in public would be cause for alarm.

I get my knickers in a twist about this because if the public opinion sways and the conventional wisdom becomes “It’s legal but unethical,” we’re cooked. Going outside with a camera will become a thing of the past for everyone but nature photographers.

“But Bill,” you’re saying. “I don’t want you to take my picture. Isn’t that my right?”

Yes. Assuming you stayed home.

“But Bill,” you say again. “I DON’T WANT YOU TO TAKE MY PICTURE!”

Well, as a reasonable human being I’m not looking to antagonize anyone. I don’t point my camera at kids. I don’t prey on vulnerable people in our society, and I generally try to be reasonable, camera or no. Sometimes people simply need a little grace. If a person asks me not to take their picture, I don’t take their picture. Sometimes photographers choose otherwise. Maybe, ironically, it’s what makes them especially good at their job. Disliked, but really good at their job.

There are consequences, of course. Maybe it’s a fight, physical or legal. Maybe it’s just a sullied reputation.

Bruce Gilden is the infamous street photographer known for his aggressive, confrontational manner. No less a photographer than Joel Meyerowitz has called him a bully. Yet watching him work is a good lesson in what is permissible when it comes to photographing people in public: damn near anything.

Am I advocating that we all act like Bruce Gilden? Certainly not. But I believe the system is already self-policing enough to keep this from becoming a widespread issue. I bet Mr. Gilden has on more than one occasion reconsidered his approach. By which I mean, if you stick your camera aggressively in the faces of enough strangers, you’re eventually bound to get punched.

I’m glad we have Bruce Gilden. But I’m glad we only have one.

I’m not advocating Gilden’s subjects choose violence any more than I’m saying photographers deserve to act obnoxious. It’s the few that ruin it for the many all around. But, frankly, just as it’s understandable (not excusable, but understandable) if Gilden catches the occasional knuckle sandwich, it’s equally understandable if one in a thousand photographers is an obnoxious twat. Perfectly balanced, as all things should be.

We can’t normalize any of it. The punchworthy behavior or the suspiciously agitated public. That said, I’d much rather live in a society with too many Bruce Gildens than none. So I think it’s time we start shouting it from the rooftops: if you don’t want to be photographed, don’t go out in public. You can always just stay home. Maybe go on social media, talk about things you don’t understand. It’s your right as an American.

Originally I wanted this sentence to end with “illegal, immoral or unethical.” But I acknowledge there’s gray area when it comes to morality and ethics in this regard. It can be seen as predatory, for instance, to casually photograph people experiencing homelessness, or other vulnerable populations. But the gist of what I was hoping to get at is that, along with it being perfectly legal, I don’t believe it to be inherently immoral or unethical to point your camera at a stranger.

For every rule there is an exception, and in this case it’s the open window photography of Arne Svenson. As a matter of policy, though, I would not consider this a best practice, regardless of whether or not you find it to have artistic merit.

This is not true of military installations, as they have their own laws. Which, frankly, seems reasonable. And which also is about the only exception. There was a ten-year period post 9/11 during which photography of federal buildings was formally discouraged if not actively prosecuted, but that’s back to being okay too.

I was encouraged by a communications professor my freshman year to memorize the First Amendment. I see his point; it’s kind of crucial to our work. Here goes, from memory: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. Or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press. Or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” It should be “laws,” plural. Otherwise, not bad, eh?

The fact that they’re often super obnoxious is not exactly helpful. You can be right but also an asshole. Try to just be right.

I usually do ask permission. But it’s out of a sense of politeness and, frankly, self preservation. The wrong person could get very upset if I aim a camera in their direction without asking. And since we’re here, wanna know how I approach strangers for a portrait? With a simple compliment and a wave of my camera: “I like your hat. Can I take your picture?” Simple as that. If photographers have a superpower, it’s talking to strangers.

What happened to Arrington vs the NY Times? Editorial use against right of privacy in a public space...

Interesting read. It's quite an odd contradiction yes: on one hand almost everyone now is a "photographer" (ah before I offend someone, "can take pictures" ;-) but on the other hand so many are against being photographed (in public).

Personally I don't really mind, but I do prefer to be 'part of the scene' rather than the main subject :-) If I happen to be in the frame, fine no worries. However, if a "Bruce Gilden" would show up like that in my face I would definitely not be amused. Just because you can doesn't mean you should ...