Should you become a professional photographer? This question has haunted me for two years. When I began Art + Math it was among the first ideas I jotted down. How would I advise a young person interested in a career in commercial photography?

I’m torn.

Ambivalence kept me from addressing the topic. I was never sure how to answer the question.

But I am now.

The question itself hides a nasty little implication. If you have to ask, something must be amiss.

I became a photographer at age 8. Dad built a darkroom not long after. I joined the yearbook, worked for the school newspaper, and studied photography in college and beyond at a respected (now defunct1) photography school. Degrees in hand, I got my first job as a photographer and maintained a side hustle interviewing amazing photographers for 20 years. I even taught photography — “commercial applications” — for a decade.

All of that is to say, I love photography. I am dedicated to photography. I am, through and through, a photographer.

So it pains me to say this.

Should you become a professional photographer? No, you probably shouldn’t.

How We Got Here

I recently wrote that photography is a terrible hobby. It was a tongue-in-cheek love letter to the medium. This is not that. If you think photography is a terrible hobby try making it your career. It is, unironically, becoming more difficult by the day.

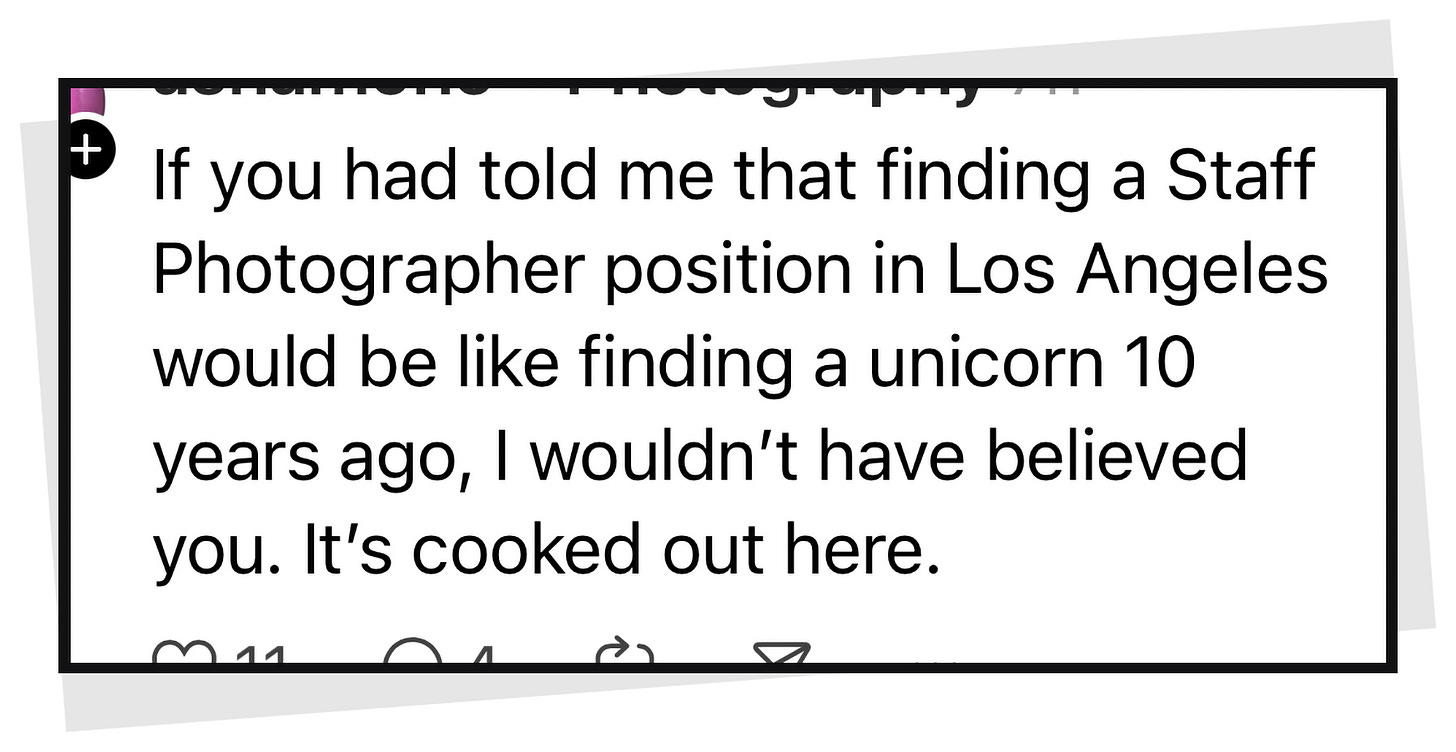

The prospects for a professional photographer in 2025 are a fraction of those available when I graduated with the last of the darkroom-trained Gen-X-ers. The trend ever since has been clear and consistent.

It began in 2000. With the release of the Canon EOS D30, digital SLRs became affordable and good enough.2 Soon, a lot of “low hanging fruit” assignments disappeared. These were the jobs that didn’t require much expertise but went to professionals in the film era because clients wanted their pictures to be sharp and well exposed. All those assignments disappeared when clients could do sharp and well exposed themselves.

Next came the iPhone in 2007. These pocket supercomputers would become the primary portal through which we’d engage with every aspect of culture — from music (another upended industry) to movies (which became short clips made by children and the unemployed).

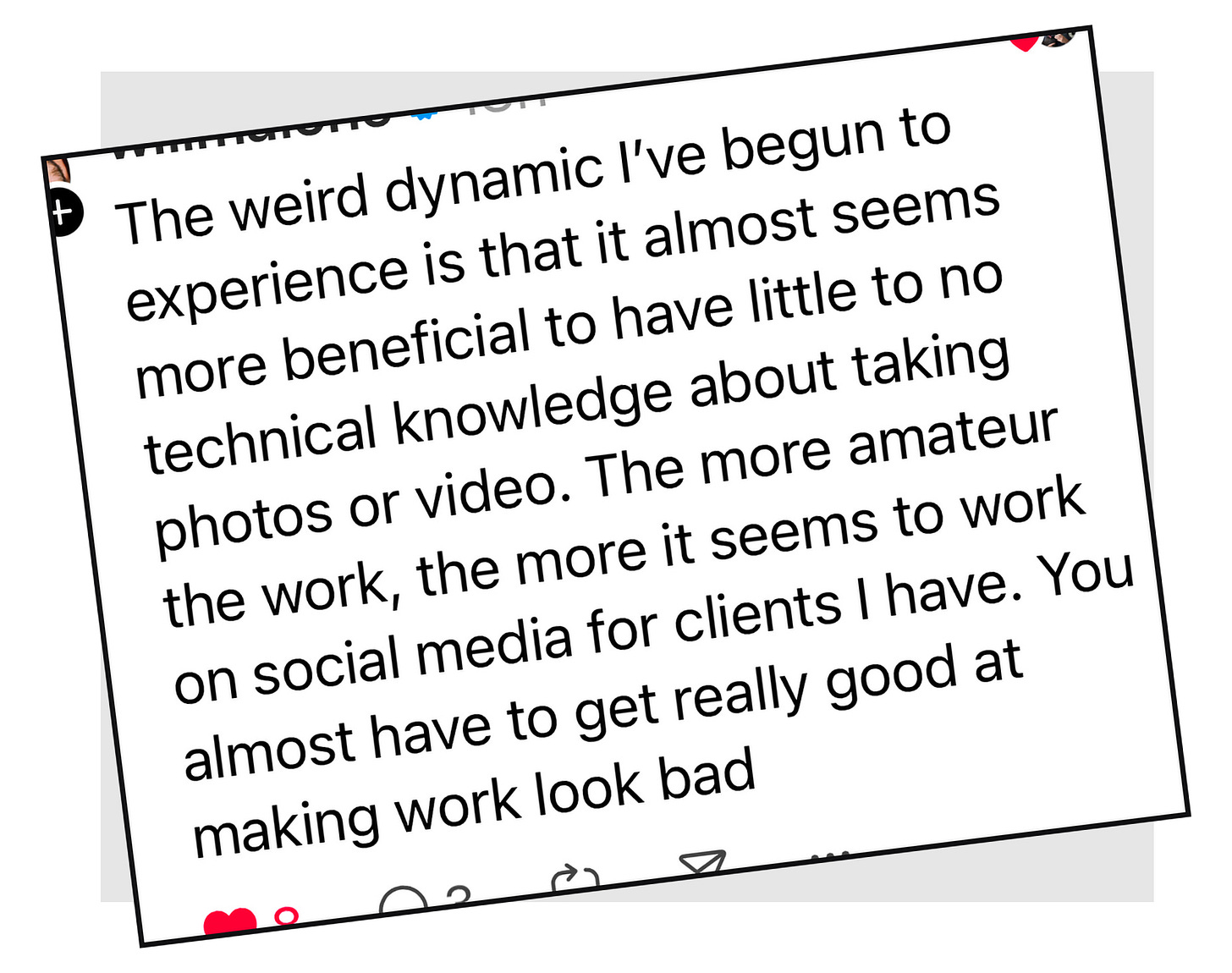

That one-two punch set the stage for the real culprit: social media. First Facebook implemented a program of enshittification to decimate publishing. Then in 2010 Instagram changed the calculus for how photographs are shared, viewed and, ultimately, valued. Authenticity (or its stylized approximation) usurped production value, and the pipeline required a lots of imagery as quickly as possible. A firehose of content, in fact.

It was a perfect storm. Photography was now commodified: more ubiquitous than ever, less valuable than ever. The law of supply and demand remains undefeated.

A Firehose of Content

When social media decimated print, it eliminated a primary place where photographs flourish. These were also the places that paid photographers to make good work via editorial and advertising. Editorials didn’t pay much, but they provided creative freedom to build the portfolios that attracted the clients with the deepest pockets: advertisers.

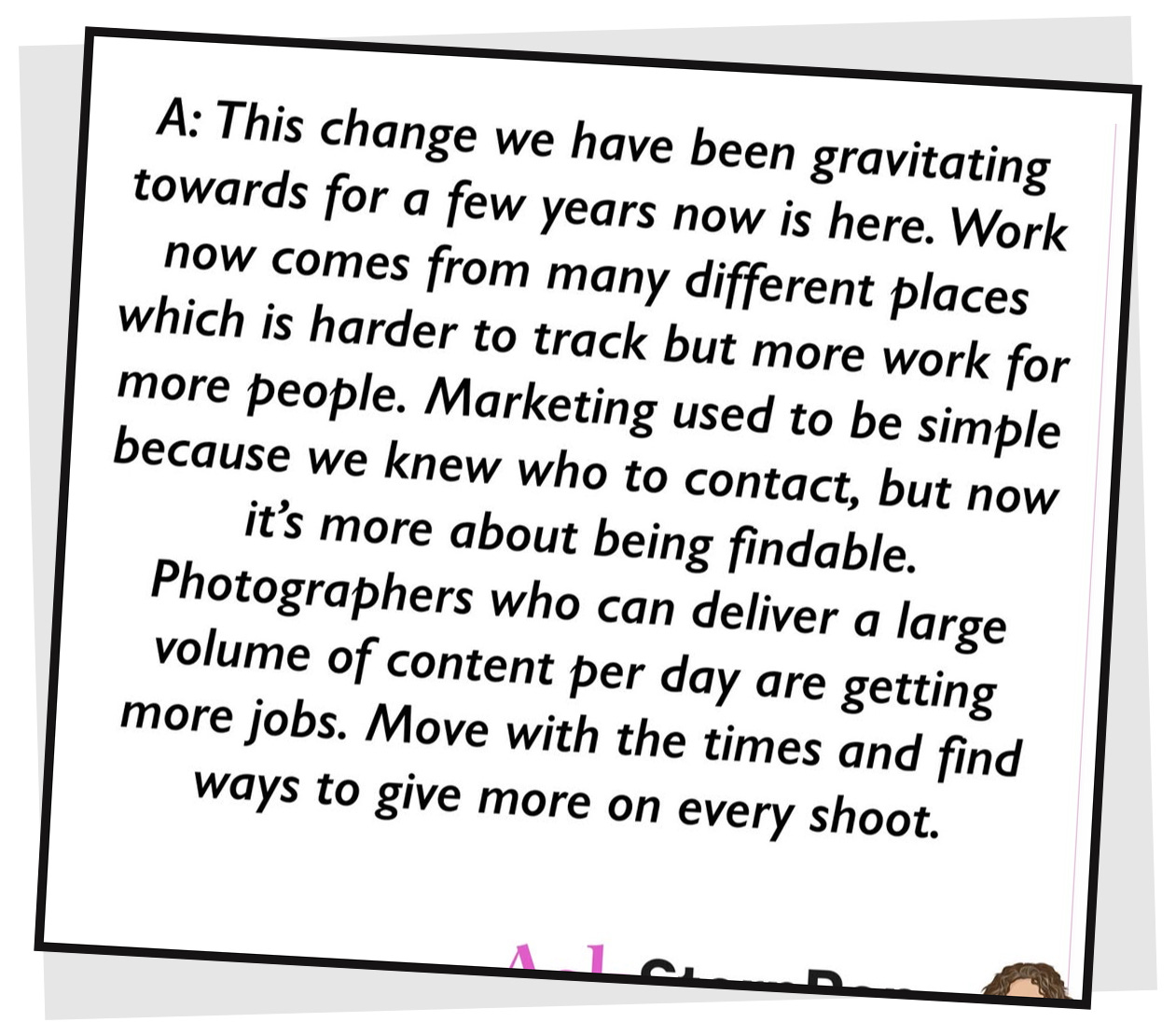

Social media changed every advertising job. For photographers, it meant that instead of hiring one of us to shoot a relatively small amount of high quality work, advertisers began spreading budgets around to several photographers (or “content creators”) to produce a high quantity of work. A firehose of content, in fact.3

In little more than a decade, advertising (and the photography that accompanies it) significantly shifted from quality to quantity. Instead of a single image appearing in print for three months, multiple images appear on a brand’s social feed in a single day.

I ask you, my fellow photographers: What is the value of an image with a lifespan of literally hours?

Seven Pieces of Personal Anecdotal Evidence

• I often photograph entrepreneurs. There are two business models I encounter more than any other: home healthcare and digital marketing. The former serves our aging populace, the latter serves the algorithm. All those digital marketing companies produce their own content in-house. They have vertically integrated photography and video production — mostly video, since the photography can be handled by whomever happens to be onsite with an iPhone.4

• In my relatively small circle all the traditional ad agencies and marketing firms I know are downsizing, eliminating offices, or closing shop.

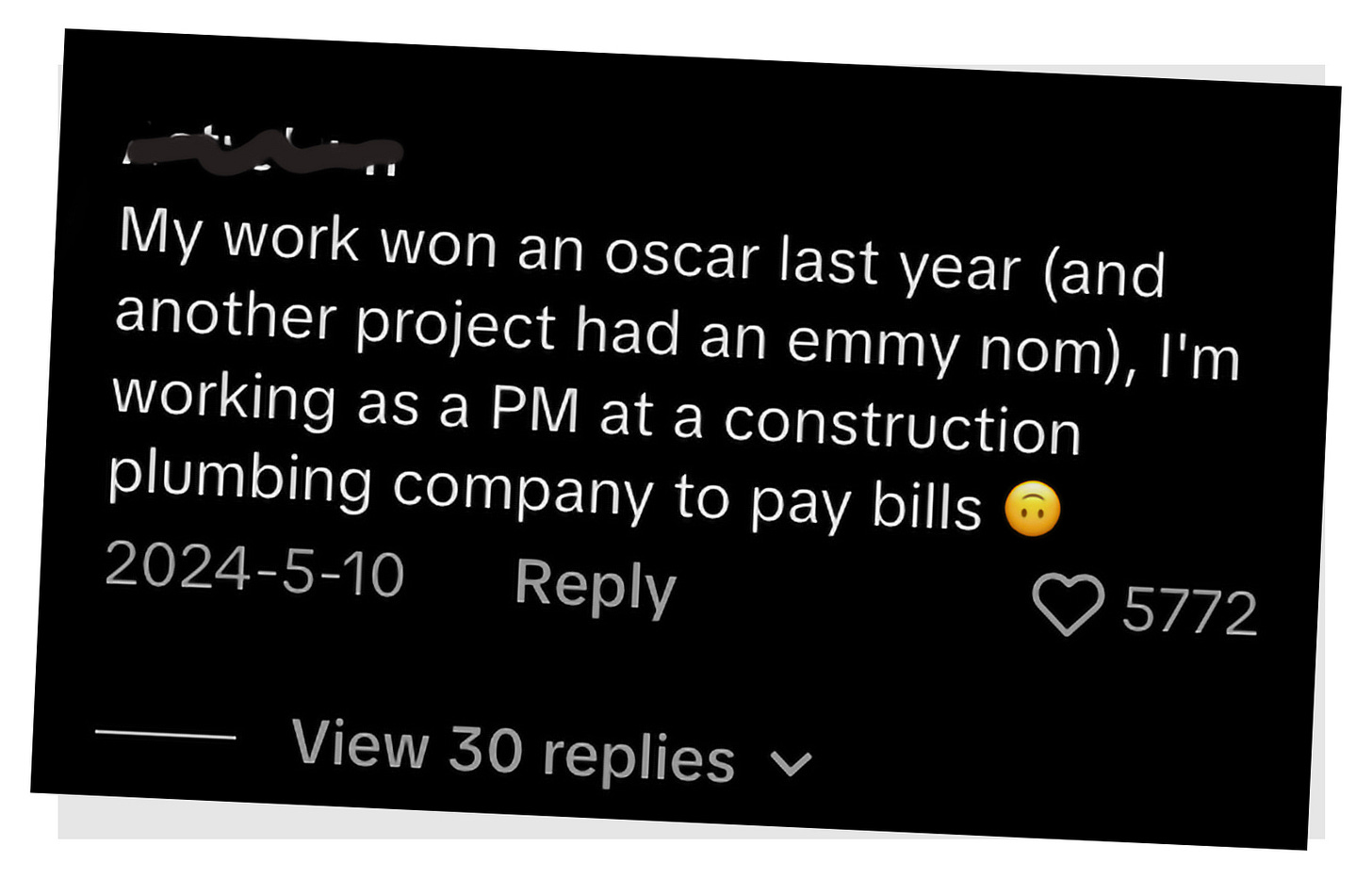

• I know multiple high-profile, brand-sponsored photographers whose primary living is earned outside photography. Flipping houses, refurbishing electronics, editing video, teaching science. (No shade. But it didn’t used to be that way.)

• In 2001, the photography magazines for which I wrote paid 80 cents per word. By 2023 the rate was 25 cents a word. Then the publisher went belly up. So did the other and the other. They were predeceased, of course, by another and another and another.5

• In 2002 I graduated from the Brooks Institute of Photography. If you wanted a career in commercial photography, Brooks was among the world’s best places to learn.6 After 70 years, it closed in 2016.

• The university where I taught (as an adjunct in a program that included a few other photography instructors) no longer offers photography as an area of emphasis. Some classes still exist, but no longer can you earn a “photography degree.”7

• The school from which I earned my bachelor’s degree in the 1900s no longer offers my “Communication Photography” major that focused on photojournalism and commercial photography. Today the department’s nearest concentration is called “Media Production” with courses on video production, audio and editing.

The Writing is On the Wall

It’s also in The New York Times. On Sunday, Steven Kurutz put into words what many of my colleagues and I have been feeling. Which is that something fundamental has changed, and it’s different this time.

Obsolete.

Kurutz interviewed writers, filmmakers, stylists, and photographers of a certain age who are flabbergasted to discover they (we) have spent a few decades mastering an art form that is no longer a viable means of achieving the American dream.

When I graduated from college in 1996, one could choose from several career paths in photography, most of which would allow you to feed a family and, eventually, buy a house. That ability is rarer today. Will it, too, become obsolete?

More than a dozen members of Generation X interviewed for this article said they now find themselves shut out, economically and culturally, from their chosen fields.

“My peers, friends and I continue to navigate the unforeseen obsolescence of the career paths we chose in our early 20s,” Mr. Wilcha said. “The skills you cultivated, the craft you honed — it’s just gone. It’s startling.”

Every generation has its burdens. The particular plight of Gen X is to have grown up in one world only to hit middle age in a strange new land. It’s as if they were making candlesticks when electricity came in. The market value of their skills plummeted.

Karen McKinley, 55, an advertising executive in Minneapolis, has seen talented colleagues “thrown away,” she said, as agencies have merged, trimmed staff and focused on fast, cheap social media content over elaborate photo shoots.

“Twenty years ago, you would actually have a shoot,” Ms. McKinley said. “Now, you may use influencers who have no advertising background.”

Read the piece. Afterward, tell me if you agree that it articulates a peculiar feeling you’ve been having. Speaking to other photographers, I’m hearing about a sense of absolution. The article seems to have removed whatever guilt we’ve been carrying about what we must be doing wrong. It’s a fairly morbid read, but at least it’ll help you feel seen. Misery loves company, right?

Since the article’s initial shock wore off, I’ve settled into a feeling of empowerment. Which is an odd reaction to finding out your industry is circling the drain. I think what I’m actually experiencing is clarity. This thing I’ve been wondering about for years, it’s suddenly very well defined. I finally have a handle on what I’m up against. Instead of playing the wrong game by outdated rules, I can start to learn how this new game is played.

To Shreds You Say?

I’m not mad I chose photography. But I am kinda sad everybody else didn’t.

Professional photographers as we know them are going away. Not dodo bird extinct, more like endangered (but without anybody raising funds to boost our population). Photography’s once great cultural relevance will dwindle. It will of course remain a medium for artistic expression, like painting and poetry. Perhaps the art world will become the best place for dedicated photographers to thrive.

Should you become a professional photographer? No, you probably shouldn’t.

This isn’t a cheeky rug pull. I’m not arguing that nobody should ever become a professional photographer again. It’s just that before you enter the fray you should know what you’re getting yourself into — which is an economic system that places decreasing value on the service you provide. It’s hard and getting harder. And there are new rules your mentors can’t teach you. So if you’re going to attempt it, you’d better be exceptionally dedicated. Like, you can’t imagine not doing it.

You should also know that your career isn’t going to be just photography. You’re likely to be a “content creator” and, most likely, your emphasis will not be taking pictures.

A thriving photographer once told me he thought every one of us needs an “and.” As in “photographer and writer” or “photographer and educator.” This was advice on building a more fulfilling and financially viable career. A decade ago it was smart. Now it’s essential.

What should your and be? I think it’s clear: video.

Print is dead, remember? You’re reading this on a screen of some sort, be it a smartphone, tablet or computer. Whatever it is, it can also play video. And advertisers know we really like video — vastly more than words or pictures. Just look at the exponential growth of TikTok and YouTube, or the decline in book and newspaper readership. When every last bit of media is delivered via screen, why shouldn’t every last image be a video?

I don’t mean philosophically, of course. I mean “why” in a capitalistic sense. Like supply and demand, capitalism remains undefeated. Since ad dollars are increasingly going to short form video, we’re going to see more of that and less of everything else.

If you want a job taking pictures in the 21st century, you’re really going to be a content creator (or filmmaker, videographer, multimedia specialist, or whatever term you prefer) whose and is photography.

The Exciting Innovation of More Work for Less Pay

For those of us having a difficult time believing that “photography is evolving” and doing more work for less pay is a youthful strategy8 that’s somehow an upgrade over the quaint old system that once allowed us to reliably pay our bills, there actually are some things I think we can do to keep being photographers in the face of a system growing increasingly focused on cheap fast content.

First, it will be incredibly helpful to find a niche (or a couple) that is not reliant on disposable social media content. These tend to be industries where good taste is essential, where aesthetics trump ROI (or at least are prioritized), where they won’t give an intern a camera and say “good enough.” A shrinking cohort, to be sure, but they’re out there.

That’s also likely to be the area least impacted by AI.9 Artists will continue to want their work accurately portrayed in its best light. As will architects and designers, and anyone in an aesthetic field will still want to see well-produced photographs of their completed projects. Corporations will (hopefully) continue wanting actual photos (or, more likely, videos) of their employees and processes. News outlets will, in theory, remain interested in facts (post-truth world notwithstanding) and thus interested in reportage and documentary photography (and video). Brides and grooms are still going to want photos (and videos) of their preposterously stylish weddings. Moms and dads will still want photographs of their kids, though perhaps less frequently what with all the pockets full of smartphones.

We can still be successful, but it’s going to look quite different. It might help to become a charlatan and start offering workshops or paid mentorships 🙄 or publish e-books about how to make money in photography. The secret, of course, is to sell books and courses on selling books and courses. Build your own pyramid scheme. Start a religion. Better yet, a cult.

TL/DR: Not Great

There’s a reason the aforementioned Times article specifically cited Gen-X creatives. Because we came up in a time of abundance, we have seen changes in the industry that mean we are paid a dime today for what earned a dollar a decade ago. This is not shouting about the sky falling. The sky done fell. The blindly optimistic say things like “you just have to evolve” but this is not evolution, it’s adaptation. By all means, adapt, of course, do what you must to stay afloat. But don’t pretend it’s evolution when it’s devolution, devaluation of the art form. We oldheads are not disillusioned or disgruntled. We just have the perspective to see the trend, and all the evidence points to one thing: the value of professional photography has plummeted. Anyone who says otherwise is selling something.

None of this makes me happy, but that doesn’t make it any less true.

It’s possible, of course, that I’m wrong and this is all just a tortuously long hiccup. Maybe there will be a backlash against fast and cheap. Perhaps print media will once again prosper. Sure everything could come back, these decade-long trends could reverse. I just wouldn’t bet on it.

It seems preposterous how quickly my beloved industry has been turned on its head. I’ve spent the entirety of my professional life, and a not insignificant portion of my personal life, fully committed to a medium that is as beautiful and powerful as ever. It’s simply no longer a thriving business proposition.

I’m shocked, but mostly I’m sad. Because I want to tell you to follow your passion as I did, encourage you to pursue your dreams, urge you to ignore the haters and become a professional photographer. But, in good conscience, I simply can’t.

Ominous foreshadowing.

Remember that combo; it’s a recurring theme.

OMG a callback!

A marketing director once rented our studio and I was surprised to see her shoot everything herself on an iPhone. I laughed it off. I should have considered for whom the bell tolls. (Spoiler alert: It tolls for me.)

Outdoor Photographer, Digital Photo Pro, PC Photo, American Photo, Photo District News, Petersen’s Photographic, Popular Photography, Shutterbug and others I’m surely forgetting. In 2015 they were all still going. The last folded in 2023.

My small cohort included students from Japan, Russia, South Korea, Thailand and Turkey.

FWIW, they paid $3,000 per semester when I was hired in 2010. They still paid $3,000 per semester on my last day in 2021.

“Youthful” translates to dues-payers doing too much for too little. At least there used to be something they could aspire to. Now the light at the end of the tunnel is an oncoming train.

Aren’t you impressed it’s taken this long to get to AI? It’s because I don’t believe it to be nearly as big a threat to professional photographers as video and social media. It ain’t gonna help, of course, but what it’s really a threat to is the fast and cheap “content” that’s already replacing traditional high-quality commercial photography.

I have a habit, which is probably very annoying to my local media operators, I call them out for bad practice.

After a long career in photography, I can't help but get annoyed at the drastic plunge in quality that masquerades as good professional standards now.

It probably will not have any effect but at least I feel better that I've pointed out to them that we are still watching.

Just today I chided my local newspaper (online) for a restaurant review with photographs that are truly dreadful.

I feel like it's not the kids that get sent out with a smart phone to try and generate this content, they don't know any better, they see rubbish online and think it's ok.

But as a now retired professional photographer I feel I should at least push back a bit and say, "that's not good enough, lift your game".

I'm sure they all think that I'm another cranky old coot waving his fist at the sky, which is probably true, but surely, we should be getting better at things, not worse.

‘The sky done fell’ That sums it up for me. Everything you say seems to come right out of my head.

Fellow GenXer here. At this point, I am hoping to straighten our finances so that I don’t have to make a living from photography anymore. And to just go back to shooting the way that first intrigued me about photography. Not sure anymore what that is, but pretty sure to find it again once the pressure of adapting and producing is gone.