We all know AI is coming for our jobs, and our free time, and our search results, and our cover letters, and our laborious coding tasks, and certainly for our marketing (budgets and content). But because all that exists outside of my head, out in the world, I don’t worry too much about how it might alter my fundamental perception of reality.

Unless of course AI ruins my brain.

No, I’m not specifically talking about the MIT study that shows we’re already indumbnifying ourselves by outsourcing formerly brain-powered activities to machines. Though that’s not exactly great news either.

I’m talking about deep, core elements of our identities. Who we are, what shapes us into the beings we be. Our innermost thoughts and ideas and, crucially, our memories.

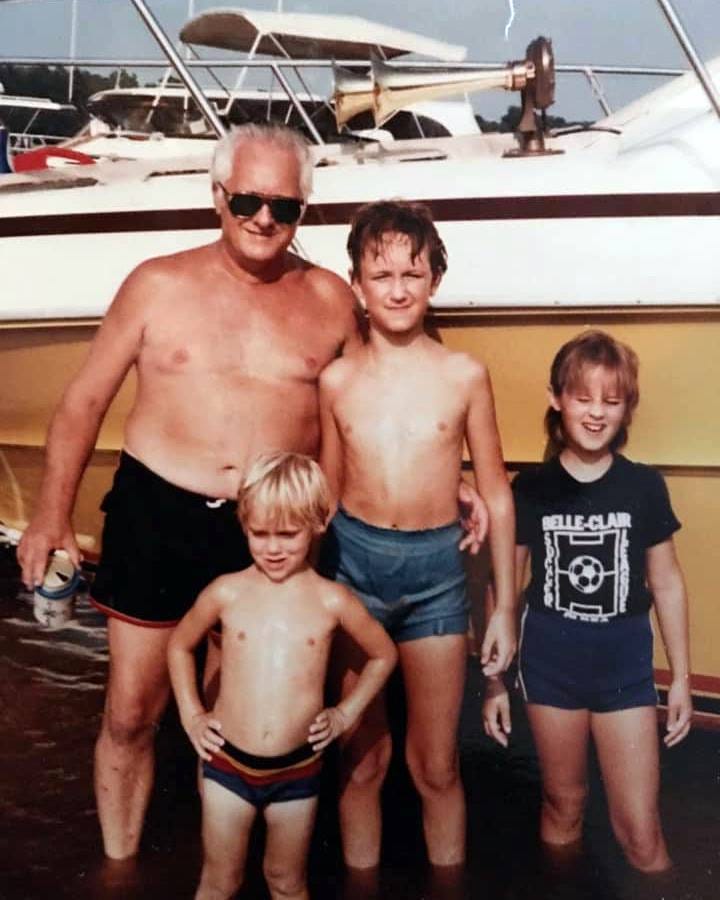

Remember as a kid how your grandfather used to take you boating on the river? No? Well that’s my memory, so it’s fine that you don’t share it. But you can have it too, if you want it.

Maybe your memories are of playing stickball in the street, or hanging out in the park with your friends, or just being alone watching TV in the dark. Whatever they are, good or bad, they’re your memories. And they contribute to who you are, to why you are the way you are. Maybe a lot, maybe a little—I’m not solving nature vs. nurture here—but I think it’s safe to say our experiences, and our understanding of those experiences, are a fundamental part of our being. Thankfully nothing can take that away from us.

Except AI.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Art + Math to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.