Saturday night is movie night at our house. We pile onto the couch and watch something loud and preposterous. I like these movies but I also like “films.” When I watch film noir, foreign films, sad documentaries and movies about gladiators, my family exiles me to the basement.

It was there one rainy afternoon when I was inspired by the 2022 German film All Quiet on the Western Front. It is intense, heartbreaking and achingly beautiful. I kept pausing and rewinding to admire the cinematography. The movie’s director of photography is James Friend, a longtime television DP with a short list of feature film credits. But the one he has, this one, earned him accolades that include an Academy Award for Best Cinematography.

Watching All Quiet on the Western Front I was envious and inspired. Envious that our compatriots in motion pictures get to bring their photographs to life, and inspired to consider what exactly I, a photographer, might learn from the work of great filmmakers. Can a photographer become a better photographer by studying cinematography?

The best cinematography works well even on pause. In the venn diagram of “photography and cinematography” there is significant overlap.

Thinking about directors I hold in high regard, each has a distinctive visual style. Stanley Kubrick, Alfred Hitchcock, Paul Thomas Anderson, Christopher Nolan.1

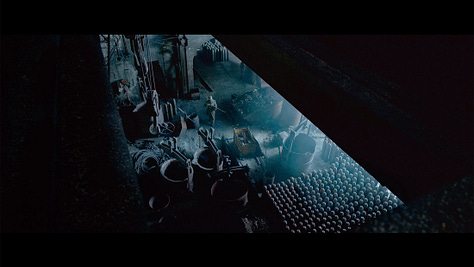

Kubrick in particular hits different. Perhaps it’s his affinity for symmetry, graphic compositions and single point perspective. Or perhaps it’s because, prior to becoming one of the most deliberate directors of the 20th century, he was a working photographer.2

Speaking of deliberate, Wes Anderson is the current king of carefully considered aesthetics. So precise are his compositions in fact, I’d argue he’s as much still photographer as film director. Not only does he (and his longtime DP Robert Yeoman) change aspect ratios as a photographer might, many scenes feature a locked down camera, creating a static frame within which the action plays out. It’s a sort of ‘cinematography with one hand tied behind your back’ as they ignore one of the primary tools at a filmmaker’s disposal and one of the key differences between stills and cinema.

Kubrick and Anderson are in rare company as directors who are the originators of their films’ visuals.3 Typically when I admire the look of a given director, it’s actually the work of a cinematographer I’m admiring. A handful of great directors do it themselves. Most are smart enough to spot genius and partner up.

Paul Thomas Anderson, for instance, long worked with cinematographer Robert Elswit (before their falling out). Elswit is an all-time great, responsible for a raft of amazing images and a Best Cinematography Oscar for There Will Be Blood. He’s got his fingerprints on many acclaimed movies—and one astonishing TV show.

Earlier this year, Netflix debuted an eight-episode miniseries praised universally for its stunning black and white visuals. The series is Ripley and its look is the work of Mr. Elswit. It’s a study in light, shadow and graphic composition. The trailer alone could stand in for a semester of film school.

Another recent visual feast was Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, the best film I’ve seen in years. (When it finished I spoke aloud to my empty living room: “Wow.”) I’ve never felt so acutely that I was watching “Hollywood movie as art.” It’s the product of a master filmmaker at the peak of his powers. But of course I was also admiring the work of a team of filmmakers, not the least of which are cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema and VFX supervisor Andrew Jackson. They create Nolan’s visual style.

Nolan, Jackson and van Hoytema have massive budgets at their disposal, but their job isn’t so dissimilar to mine. It occurs to me that Hollywood filmmaking is much more akin to commercial photography than, say, journalism or fine art. Much like advertising photography, talent is hired to appear on camera, and talented crew members collaborate to bring several elements precisely together—wardrobe, locations, props, sets, hair, makeup, grip… Advertising photo shoots are little movies. Movies are big advertising shoots—though, hopefully, with a higher-minded aim than simply selling more mayonnaise.4

Which begs the question: if their commercial film productions look that good, why don’t my commercial photography productions look better? I don’t have any excuse, really. Sure, my budgets are much smaller and my time constraints much greater, but I, too, get to put the lights where I want and tell the talent where to stand. How is that any different than Kubrick? Is it just a matter of taste?

All of that is to say, I’ve come to the realization that my work would benefit from being a bit more cinematic.

Can I apply the techniques of master filmmakers to my still photography? I think I can. After all, cinematography is just still photography 24 times a second.

Which begs the question: what, exactly, are the techniques that make them great?

John Altman literally wrote the book on lighting for cinema, a refreshingly classic take on deliberate lighting technique that taught me, among other things, the benefits of using a “test light.” My own education included significant time spent studying classic portrait lighting patterns based on early Hollywood techniques—one even named for the movie studio that popularized it.5 A gaffer on a video set once taught me about book lighting to create exceptionally soft, indirect light. Cinematographer Marshall Adams ensures eyes sparkle, even from the darkest shadows, using a low-power LED to add a catchlight and only a catchlight. Roger Deakins uses a technique called “cove lighting” which wraps light nearly 180 degrees around a scene for more pleasing highlight-to-shadow transitions while providing the talent the freedom to move freely through the frame without resetting.6

That’s all well and good, but great cinematography is more than just great lighting. In fact, I found while studying7 the work of great directors and DPs that composition is every bit as important. Or it is for me at least, because strongly graphic shots are the ones I find most impressive.

Watching movies I began making notes and examining frames. A few themes emerged. Such that I have—finally—compiled this list of ten things cinematography taught me about photography.

Ten Things Cinematography Taught Me About Photography

1. Silhouettes are compelling.

2. Simplicity is powerful.

3. Symmetry feels good. Pattern, geometry, leading lines, S curves too. (Study Stanley Kubrick and Wes Anderson for more.)

4. Shadows add mystery, and mystery is your friend. Not everything needs a fill light. When in doubt, turn the face toward the key.

5. Wide angles tell a whole story. They provide context and an air of authenticity. Add a person for scale and the image becomes even more powerful.

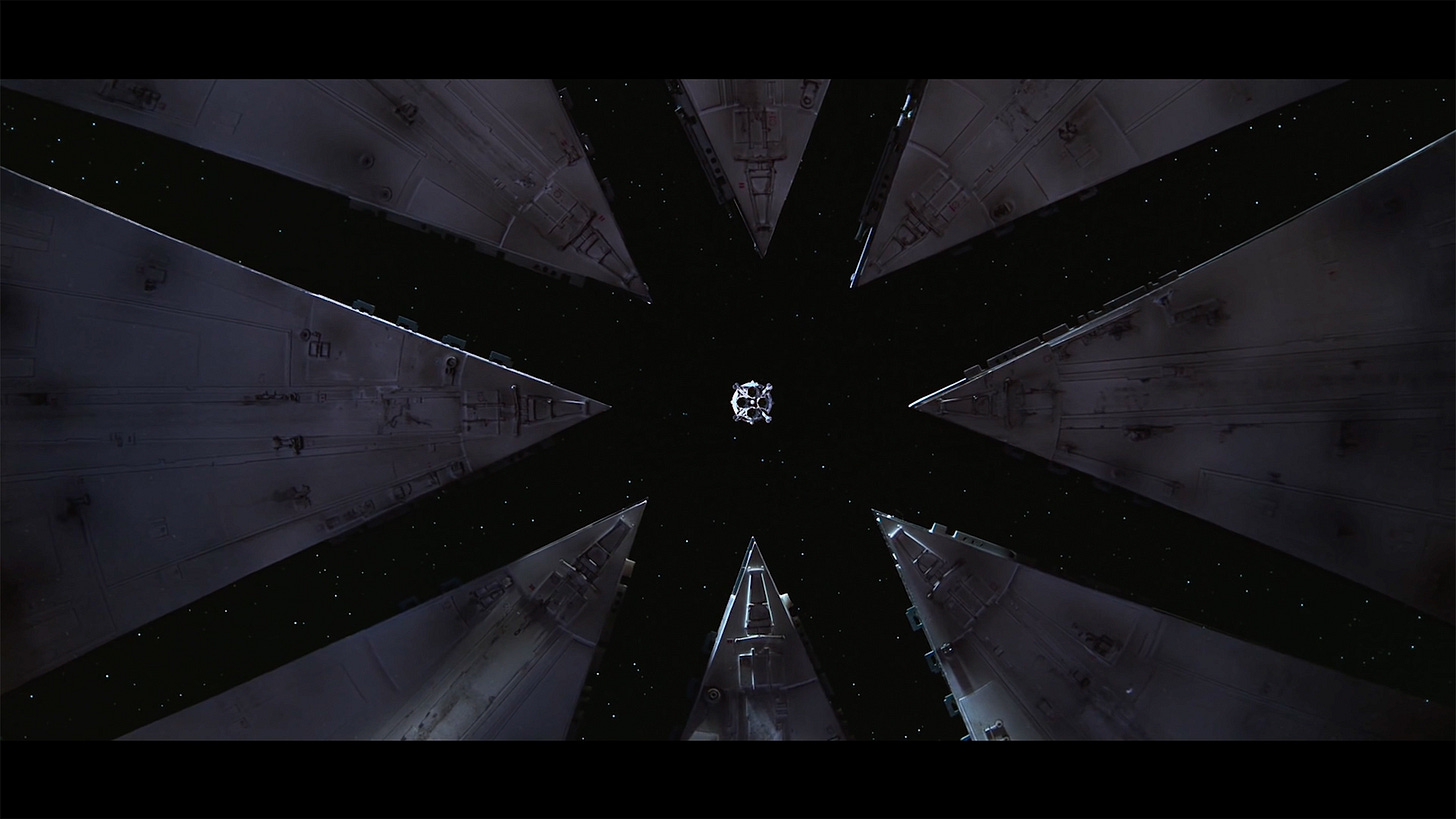

6. Unusual perspectives—top down (crane/aerial) and looking up (Quentin Tarantino’s trunk shots, for instance)—are never not interesting.

7. Layers keep the eye interested. Foreground, middle ground, background. Their effect is more than additive, it’s exponential.

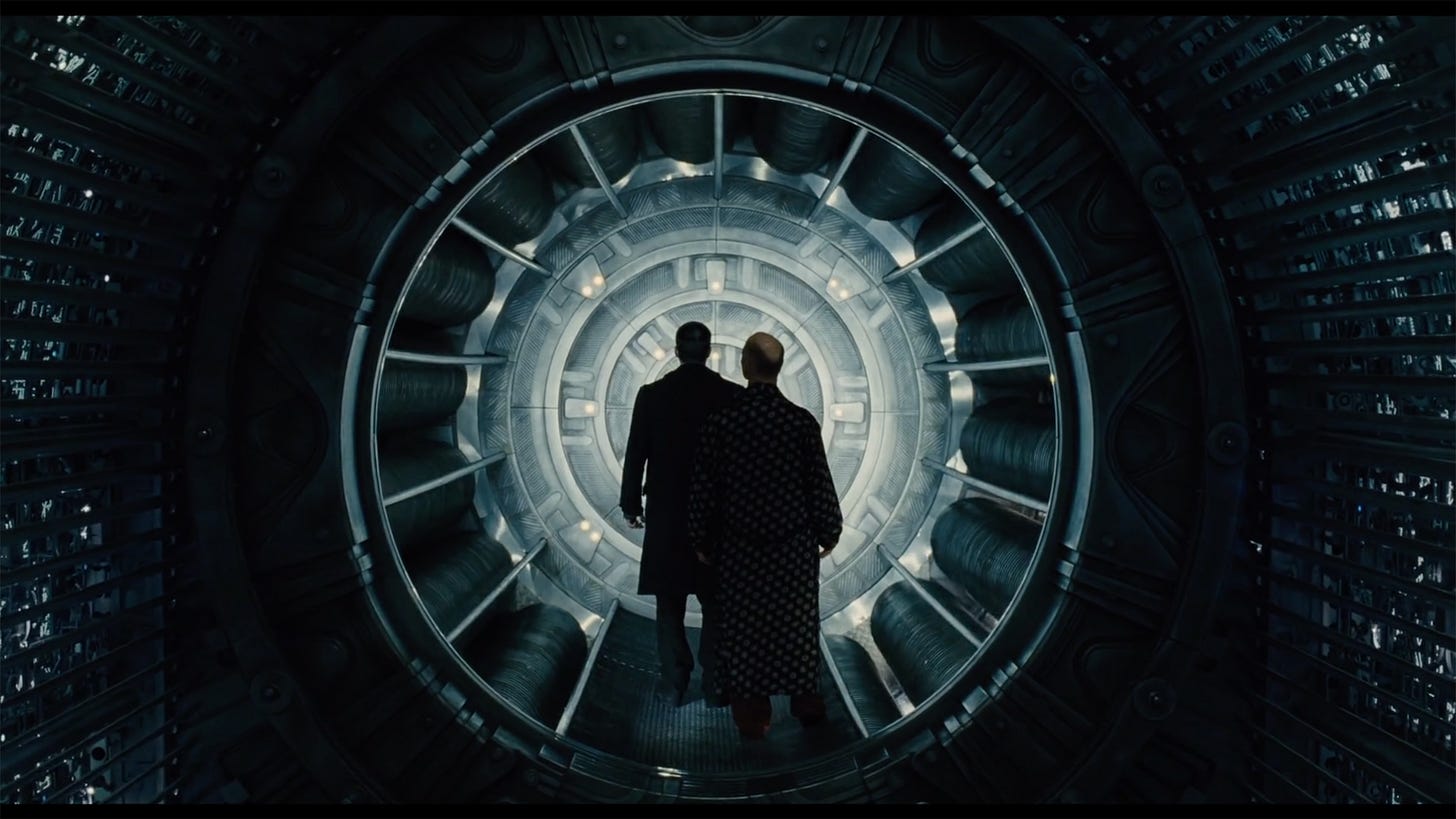

8. Frame within a frame, by virtue of adding depth and graphic interest, pulls the viewer into the scene.

9. Light and shadow are storytelling tools, but so is color. The interplay of warm and cool tones is a proven way to create tension. (Kubrick did this especially well in Eyes Wide Shut. Roger Deakins does it nicely in Sicario.)

10. Somewhere in the middle of compiling the above, I realized this is all fairly basic “composition 101” stuff. Which makes me think perhaps I simply don’t dedicate enough attention to these basics—at least in the way the best cinematographers do. The good news is, that’s the kind of thing I should definitely be able to implement. The bad news is, it still won’t make me the next Stanley Kubrick.

The list of directors of whom I’m particularly fond is not especially unique. Along with the aforementioned masters, my shortlist includes David Fincher, Michael Mann, Bong Joon-Ho, Kathryn Bigelow, Spike Lee, The Coen Brothers…

Kathryn Bigelow was a sculptor and painter. Spike Jonze was a photographer. David Lynch is still a photographer. Gordon Parks was a photographer turned director. Emmanuel Lubezki has an amazing Instagram. Roger Deakins published a book of his photographs. The list goes on.

They do collaborate with cinematographers—Geoffrey Unsworth, John Alcott and Robert Yeoman, most notably—but the directors do appear to drive the aesthetics.

It could be argued that the 25th in a series of money grubbing comic book movies is actually more cynical than a condiment commercial because at least the commercial is honest about its lowbrow aims.

George Hurrell and Clarence Sinclair Bull offer ideal examples of these techniques executed to perfection.

He prefers unbleached muslin because it adds pleasing warmth to skin tones. When working on location he’ll gaff tape it to the wall. I’m already learning things I can apply to my own work.

Over the preposterously long time I spent working on this piece, a few resources were invaluable. First is a YouTube channel called ”The Beauty Of“ which showcases great scenes from master directors and DPs. The website Filmgrab is a database of great shots, keyword searchable. (It’s a free resource that’s a stripped down version of the industry standard for researching cinematography, Shotdeck.) I also enjoyed a few interviews with cinematographers, especially this Cinematographer’s Roundtable which features several of the greats mentioned above. (In it, they discuss other great films and directors that inspire them: The Battle of Algiers, The Wages of Fear, Francois Truffaut, Jean Pierre Melville, David Lean, Andre Tarkovski, Akira Kurosawa, Sofia Coppola, Wong Kar-Wai, Bernardo Bertolucci, Sergio Leone…) And Roger Deakins, who just might be one of the best ever to do it, breaks down his most iconic films in this video. “Reality doesn’t have to be naturalistic,” he says. “it doesn’t have to be exactly the way light is. You want to create a coherent world for the audience, so that they believe.”

Wow! I enjoyed this👏

More content like this! So good!!!