Arguing With Dipshits in Public

Manners matter less than ever online and more than ever on the street

I think they should rename social media. The term is misleading. I think a better name would be “Arguing with dipshits in public.” It seems to be made for that.

Most of the dipshits I’ve argued with would say the same about me, I’m sure. No doubt I’m just as much of a dipshit to them as they are to me. The difference, of course, is that they’re wrong.

I don’t set out to argue on social media, truly. I enter with a positive mindset, aiming for genuine discussion. It should make us smarter but it has the opposite effect. It should be the perfect place for a free exchange of ideas about topics we find interesting and important. Not about politics, per se, but rather things like photography and culture — the stuff I write about here.

It’s become so difficult to have a genuine, thoughtful discussion online that you’d think I’d be smart enough to stop trying. What can I say, I’m an idealist. “Be the change you wish to see” and all that. I want things to get better. I want us to be better.

Mostly, though, I’d just like to have a thoughtful conversation about a topic I’m interested in.

When I’m chatting in public with a dipshit, I try to take the high road (mostly) and don’t stoop to name calling (mostly). When I get insults thrown at me I think, well, I must be right because they’ve stopped presenting facts and are now just calling me a dipshit. I would never.

Just the other day I discovered, much to my surprise, that what I thought was an earnest exchange of ideas was in fact just another dipshit itching for a fight.

The topic du jour was something I believe to be quite important. It’s also a subject about which public opinion appears to be changing. And, funny enough, it was about how we treat one another in public.

I stumbled upon a discussion about photography in public places, a topic which has been well covered in these pages. I see this sort of thing talked about increasingly, but I don’t think the folks who espouse one popular idea have considered its ramifications.

Their complaint boils down to this: “Photographers should not take pictures of people in public without permission.”

That seems like a bad idea. Being able to take pictures in public — even those that include other people — is a fundamental American freedom. It’s most essential, anywhere and everywhere, for a free press.

That’s the crux of my argument, and while I don’t think I can be convinced otherwise I can become better informed about why people believe their opposing view to be a good idea. Perhaps there’s something I’m missing, or something to consider in a new light.

My most recent public interaction went something like this:

“It’s rude to photograph people without their permission,” someone wrote. “What about the right to privacy?”

“I don’t understand the idea that being photographed in public is an invasion of privacy,” I replied. “Legally, in the U.S. at least, there’s not much of an expectation of privacy in public. Morally, too, I don’t think of this as an ‘invasion’ when you’re walking down a public street. You’re clearly not the only one who feels this way, though. It seems to be a growing sentiment. Perhaps a response to social media? Or surveillance culture? But public is not private, no?”

How reasonable was that? Pretty good, if I do say so.

“I think it’s imperative that people have the right to use a camera in public,” I added. “Any language to the contrary strikes me as damaging to freedom of expression, freedom of the press. I think you should absolutely have the right to privacy when you are in private. I think you should absolutely have the right to control the commercial use of your likeness. But these are very different from the idea that photography is some sort of violation.”

“It’s like voyeurism,” they countered.

“I pretty firmly believe if it’s public it’s fair game,” I wrote. “I disagree that anything I see in public could be considered voyeurism. It can be rude and aggressive and largely inappropriate but I don’t see how in public it could ever be voyeurism. My issue is with the idea that ‘we shouldn’t take pictures of strangers in public without their permission.’ I think this is dangerous.”

“Would you say paparazzi work isn’t voyeurism?” they responded.

“Voyeurism implies seeing something you shouldn’t,” I replied, “something otherwise hidden from view. I think if you’re walking down the street that’s hard to see as voyeurism. Do I think paparazzi can be harassment? Absolutely. I don’t think the camera absolves you from responsibility. There are plenty of gross and inappropriate ways photography can be used. My belief is that this is an unfortunate side effect that should be policed by means other than ‘you can’t take pictures in public without permission.’ You shouldn’t harass celebrities, or exploit vulnerable people, you shouldn’t prey on unsuspecting people. All of these things are exceptions to the vast majority of photographs made in public, which are utterly benign.”

To be clear, most of the folks entering the discussion in opposition to my ideas were not rude. It felt, for a brief and shining moment, like thoughtful people who held differing opinions were sharing them in an effort to better understand one another.

Then a dipshit showed up.

He was disguised at first, but once I said that I thought a ban on taking pictures in public might have ramifications for a free press he called me a twat and told me to fuck off. Which I interpreted as him conceding my point. Victory!

I wasn’t trying to win an argument, though. Frankly I didn’t even realize we were arguing. I genuinely thought we were engaged in friendly discussion. I only hoped to provide a little pushback on an idea that might sound appealing on the surface but which, I believe, would have terrible side effects. And not just for photographers.

When journalists can’t wield cameras in public, those in power more easily oppress us. When artists can’t use cameras in public, our views are more rarely challenged. When regular people — families and friends and tourists — can’t take pictures in public, the world becomes a smaller, duller place. Facts would be more easily replaced by lies and opinions. Misinformation — not exactly in short supply — would become even more prevalent. And to what end? So someone on a public street can feel like they’re in private?

Let’s not forget that significant protections already do exist. In the United States, I can’t publish your likeness for commercial purposes without your permission. I can make art that includes you if you’re in public, and I can make news photos that include you too.1 But I can’t harass or assault you. The rules for behaving in public are fairly well established.

So why is the expectation of privacy changing?

The Electronic Frontier Foundation blames surveillance culture when it says we are “at risk of exposing more information about ourselves in public than we were in decades past.” They make a strong case that there is in fact some reasonable expectation of privacy in public. Namely, it’s reasonable to expect that security cameras and smartphone tracking won’t be used to monitor our whereabouts for an extended period of time.

As far back as the 19th century, great thinkers argued that the right to privacy, at its core, amounted to “the right to be let alone” and that one’s property protections extend to every form of possession, even the intangible. That sounds to me like the foundation for the right to control where and how your likeness is presented. So maybe this public privacy idea isn’t new so much as newly relevant.

These exceptions to “no right to privacy in public” seem reasonable to me. What doesn’t is the idea that a photographer with a camera is inherently offensive. How the picture is used might be, but the simple act of viewing the public sphere through a lens? I have a hard time accepting that as a violation.

My instinct is to blame these changing social mores on social media, where billions of images are shared every day. We control what images we share — often images of ourselves — so we feel as if that ownership should stick with us wherever we go. We photograph ourselves in our pajamas, in our beds, in our birthday suits, in our bathtubs, in every situation imaginable, and then we share those images with the world. But we do it on our terms, and we balk at the idea of giving up that control to some stranger on the street.

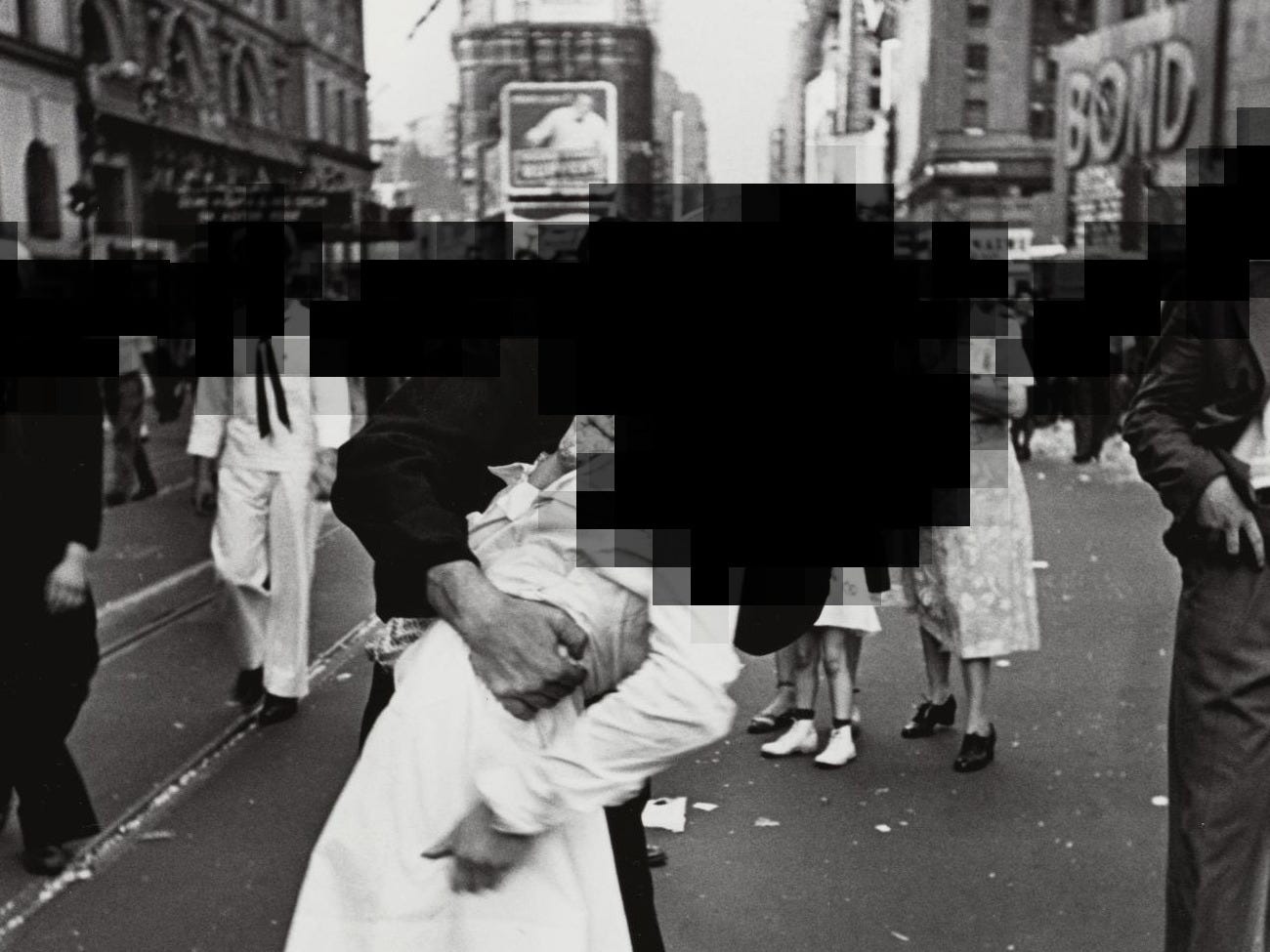

Imagine all that would be lost if we eliminated photography of strangers in public.

I’m not a street photographer, so this isn’t brazen self interest. I’m used to being hassled when I take my camera out in public. But a photographer with a camera isn’t the same as a government with a camera. To empower the unstable among us to insist upon their right to restrict where I aim my camera — rights which in this context do not meaningfully exist — seems immensely dangerous. For a public already primed to protect personal liberty above all else — including the collective good — this idea, gently spreading and cloaked as common courtesy, is a recipe for disaster.

And so, even if they’re civilized about it, people are going to continue popularizing this bad idea. Maybe we can redirect them, though. Maybe instead of “no cameras in public” we could get behind “don’t be a jerk with a camera.” Carve out an exception for Bruce Gilden, but then the rest of us do our best to behave (mostly). The golden rule is great when it comes to interacting with strangers, camera or no. Treat people as you’d want to be treated. I think that goes for social media as well.

It’s a big leap from “people should be more polite” to requiring permission to take pictures in public. So I think we have to speak up, push back — politely, reasonably — and point out the problematic consequences. Even if it means some dipshit comes along and calls you a twat.

With some restrictions. I can’t deliberately embarrass you, for instance.

The courts have held that photos in public are akin to free speech, but we’re now seeing free speech threatened. These are both dangerous erosions to our fundamental freedoms. Both are ethical issues. Making maliciously awkward photos of people in public is inexcusable as is saying irresponsible things on (anti)social media. Both are ethical matters, and more than ever ethics don’t matter, and this has terrifying long term consequences for society.

In some cases I simply agree that I am all of those awful things I was just called, suggest we set that aside as a non-issue, and suggest we discuss the issue at hand with facts and citations of sources. Often things stop right there. What one finds out is that we end up dealing with someones opinion, based upon whatever, but held close as a part of ego. It's hard to have an exchange in that scenario.

As for shooting in public; it's tricky. We have laws and manners, not the same thing.