7-13-2024

A day that will live in pictures

I don’t write about politics, but on a day such as this I believe it’s worth pausing regularly scheduled programming.

I’m surprised by the intensity of my personal reaction to the attempt on former President Trump’s life. I feel profoundly sad that an American presidential candidate was inches from assassination. As former President Obama wrote, “There is absolutely no place for political violence in our democracy.” That this is the reality of our current situation is maddening. That a person has died because of their support for a political candidate is tragic.

Because this is ostensibly a publication about photography, I want to call attention to the role photography has played in our understanding—or really my understanding—of breaking news over the last 24 hours.

The first report I heard was in passing and did not convey the severity of events. It sounded initially as if the former president had simply been taken from the stage out of an abundance of caution. Soon that report was accompanied by a photograph depicting Mr. Trump on the ground, blood on his cheek. It is so intense, so impossible, that it didn’t seem real. In the age of AI the initial reaction is that it simply cannot be.

This is, of course, the most dangerous consequence of AI image generation. No doubt we will soon see fictional illustrations passed off as fact, in this case as well as with every newsworthy event from here on out. What an incredibly dangerous propaganda tool. What could be more dangerous than deliberate disinformation supported by photographic “evidence.”

Real photographs being dismissed as fake, fictional illustrations being accepted as fact, and our eager willingness to accept anything that supports our own personal narratives. This is the state of society today. As technology improves it’s only going to get worse. Reality will be harder than ever to define. Impossible, even.1

In moments like this I’m struck by how important functional legitimate news organizations are when it comes to policing and preserving democracy. Editors and producers vetting information are often dismissed as biased and manipulative. Yet the standards set by major news organizations are incredibly valuable in a world where anything goes on social media. Anything does not, and should not, be construed as factual and newsworthy by mainstream media. So while I turn to social media for rumor, gossip and word on the street, I turn to professionals to vet and verify the scuttlebut. It’s not a perfect system, of course, but it’s the best chance we’ve got. Get your news from someone who gets fired if they get it wrong.

I find myself turning on the TV when breaking news is happening. What I saw first last night was video footage of the rally, which did a great job of outlining the basics. But what CBS news interspersed with the video clips were images that provided more detail, were more emotional, and I would argue exponentially more powerful. These photographs were made by professional photojournalists covering the event who, after shots rang out and the crowd ducked for cover, sprang into action to document glimpses of fact amid the chaos.

CBS television news knows something we do too—or at least something many of us have certainly sensed. When compared to video, still photography hits different. It’s not better at separating fact from fiction, per se, but because it condenses a narrative to a fraction of a second, that story becomes inevitably more profound. Video often provides broad, even more complete understanding, But photographs dive deep into the details, distilling the essence of the thing. At least that’s my take as I sit here watching TV news.

The photograph that I’m seeing most, and which I expect will go on to visually define this bit of American history, was made by Anna Moneymaker, a staff photographer with Getty Images in Washington D.C. Her image strikes me as all but miraculous on a day full of miracles.2 The blood on the cheek, the open mouth, the empty hand, the dramatic light, the American flag, upside down as in times of distress. A momentous photograph.

Moneymaker interned at the New York Times in 2020, covering Capitol Hill and The White House, where she no doubt bumped into another photographer who was at yesterday’s Butler, PA rally, Evan Vucci. He made one of the first photographs of yesterday's events that began to clarify for me the gravity of what had occurred. I stumbled across it on social media, and there amid the vitriolic trolling it was still catching attention in the comments for its ability to tell a story in a single, powerful frame.3

Vucci is a Pulitzer Prize winning photographer for the Associated Press—an opportunity that originally arose for him courtesy of another photographer in attendance yesterday.

That was Doug Mills, a New York Times photographer and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner. He helped Vucci secure his first opportunity as a freelance photographer working for the AP. Both made soon-to-be-iconic images yesterday.

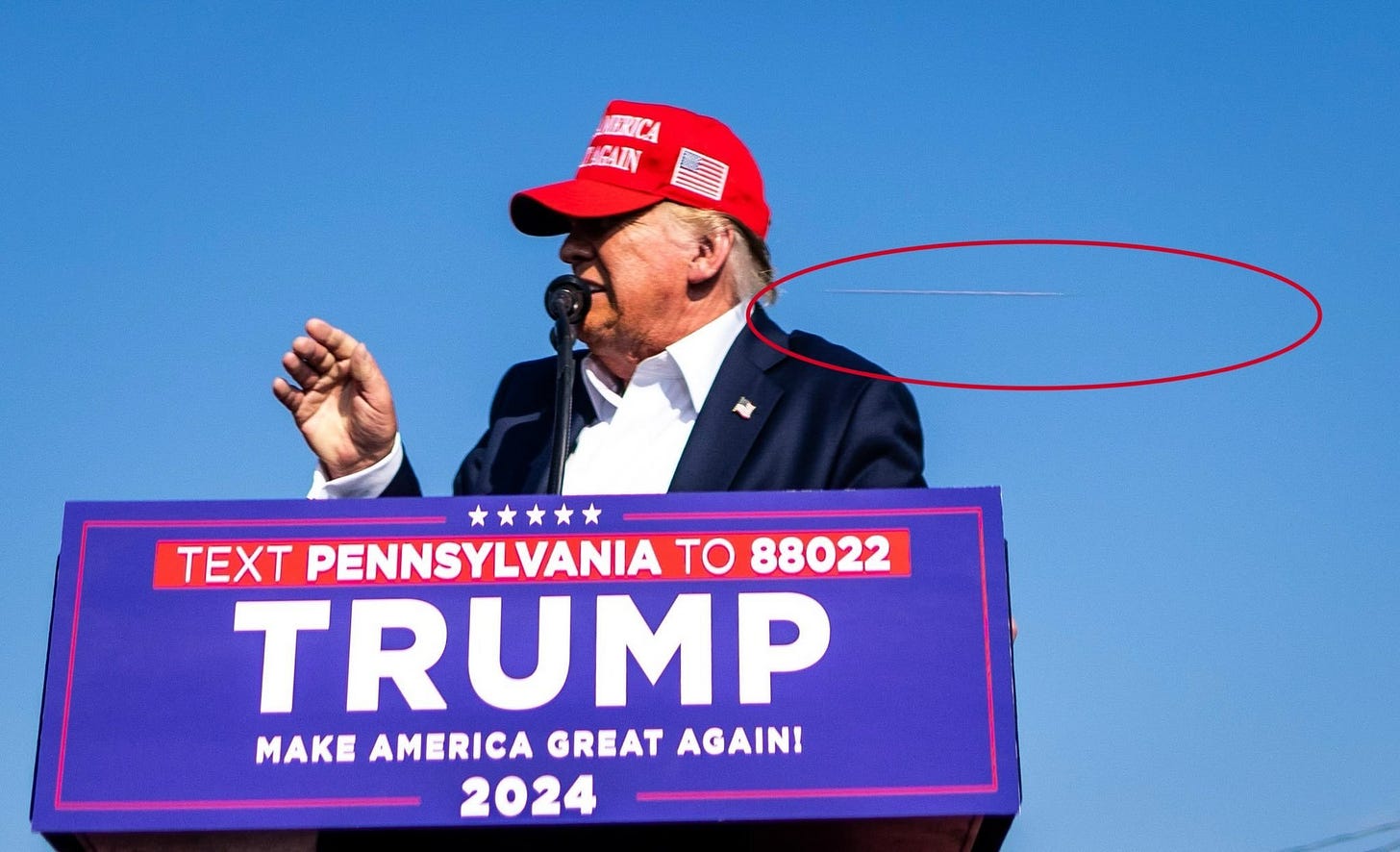

The image captured by Mills is astonishing not only as a historical record but as a technical achievement. It depicts a bullet narrowly missing the former President, a blurred streak passing by his head. A seemingly unbelievable image that will no doubt be confused for AI, or accused of it, and surely used to stoke the fires of conspiracy given the near impossibility of its creation.

We must remain vigilant in our ability to distinguish fact from fiction, both when the latter appears based in reality as well as when real photographs seem too good to be true.

As social media fills with commentary from all sides, casting blame, trolling for a fight, perpetuating conspiracy theories and sowing disinformation-powered division, I hope to resist the urge to jump into the rhetorical mud and drag the discussion even lower. I am reminded of the phrase, “Never ascribe to malice that which can be attributed to incompetence.” Our brains want to make order from chaos. It’s a natural tendency but it can lead us astray. Sometimes chaos is all there is.

I hope my fellow Americans will join me in unilaterally rejecting violence, political or otherwise, in an effort to prevent its normalization. Likewise, I reject unhinged rhetoric that amps up tensions and allows us to forget our common bonds—as Americans, yes, but primarily as humans.

There is an oft-quoted curse disguised as a blessing: “May you live in interesting times.” Here’s to hoping things get much less interesting soon.

For this reason, tech companies must adopt standards that not only embed permanent code identifying AI generated images but also utilizing technology such as Google’s SynthID to identify such images after the fact—as they are uploaded to social media, for instance.

The commercial photographer in me notes that this historic news photograph can be licensed for $175. Make of that what you will.

It was also being called into question as a possible AI generated image. The sort of blind speculation that makes social media so appealing at moments like this, and so unreliable.