When Ansel Adams Got a Government Job

The most famous photographer of all time was just like you and me

I’ve been reading more than usual about Ansel Adams. I don’t have a whole lot of knowledge about the man, and no burning passion for or against his work. I admire him, of course, as anyone with eyes should. And I marvel at the technical heights he achieved, as well as what he accomplished as an artist, as an environmentalist, and on behalf of the medium we both love.

What I find most interesting, though, is how Adams was fundamentally like me: a working photographer. I think he would’ve had a lot in common with my colleagues and compatriots. Writing for the New York Times, Jonathan Blaustein called him “a hyperactive workaholic who routinely worked 18 hours a day, seven days a week.” He lived apart from his family, traveled often, and generally worked too much because he had to. I like to think I’m one up on him there, work/life balance wise.

He may be the most famous photographer of all time, but he was doing it before photography was broadly accepted as fine art. Which means he was working because he had to, printing more to pay the bills, taking assignments to try and turn a profit. Sound familiar? It does to me.

I’m fascinated by the fact that the world’s most famous photographer was, in my lifetime, a working man. At one point, he even took a job working for the government.

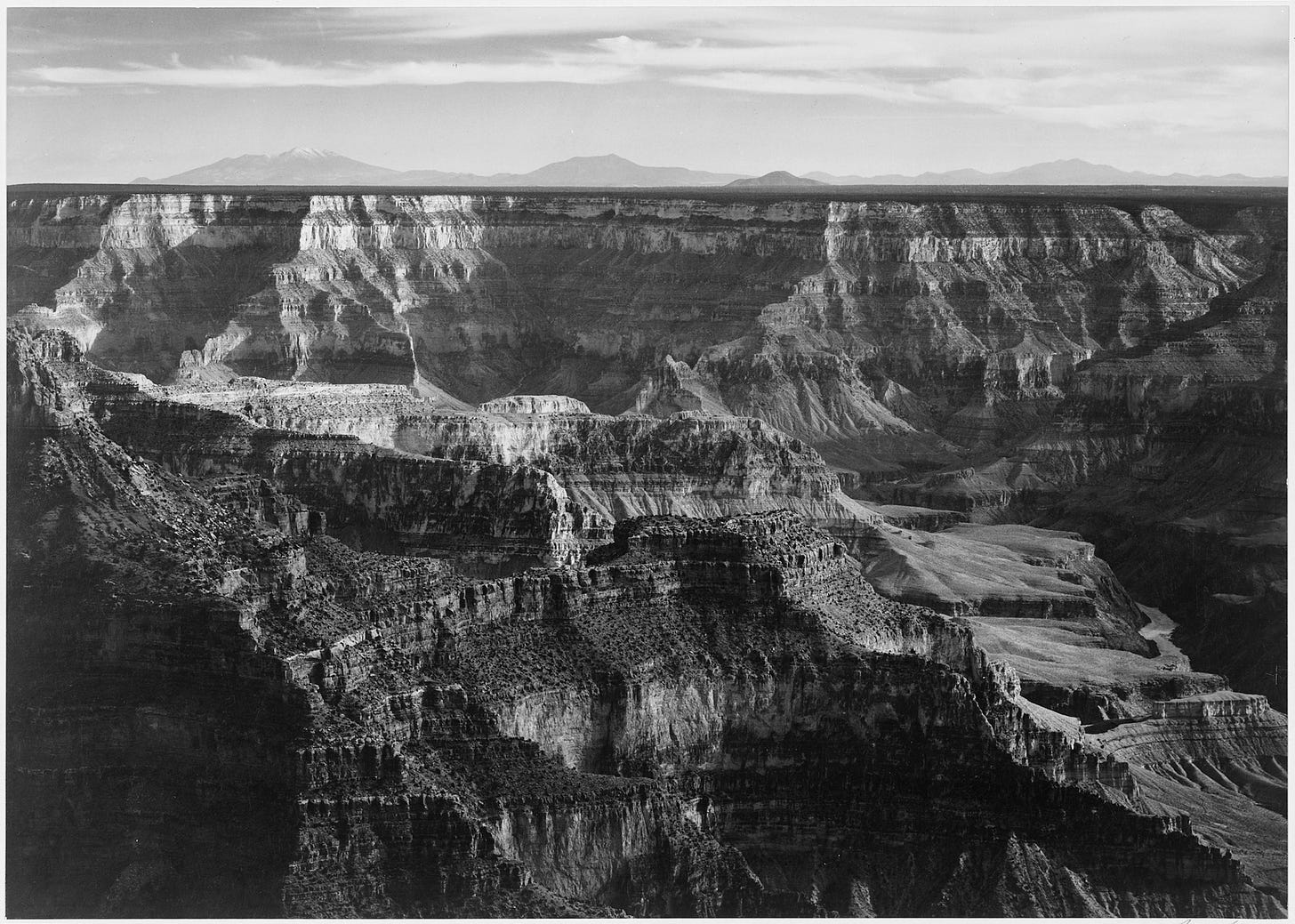

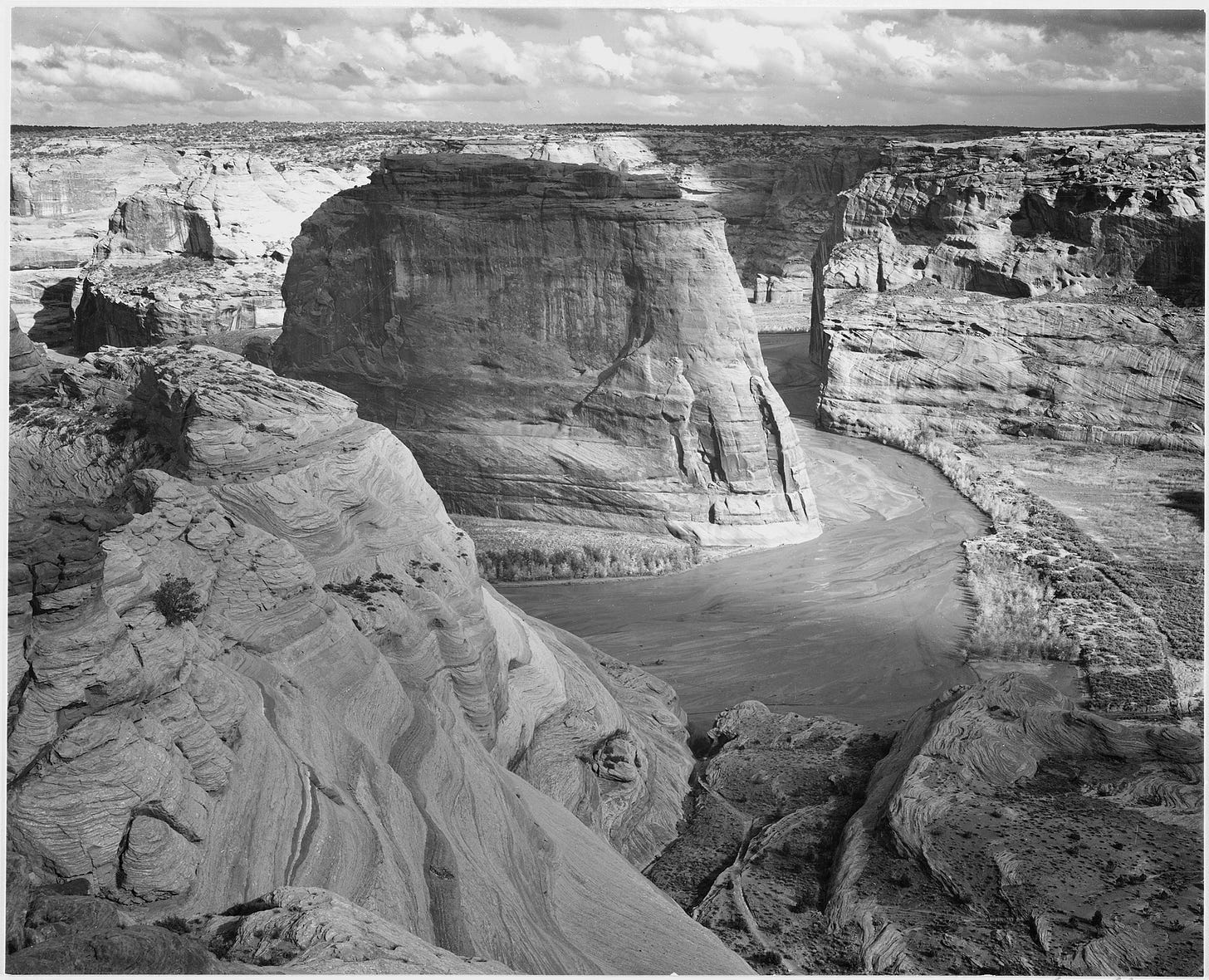

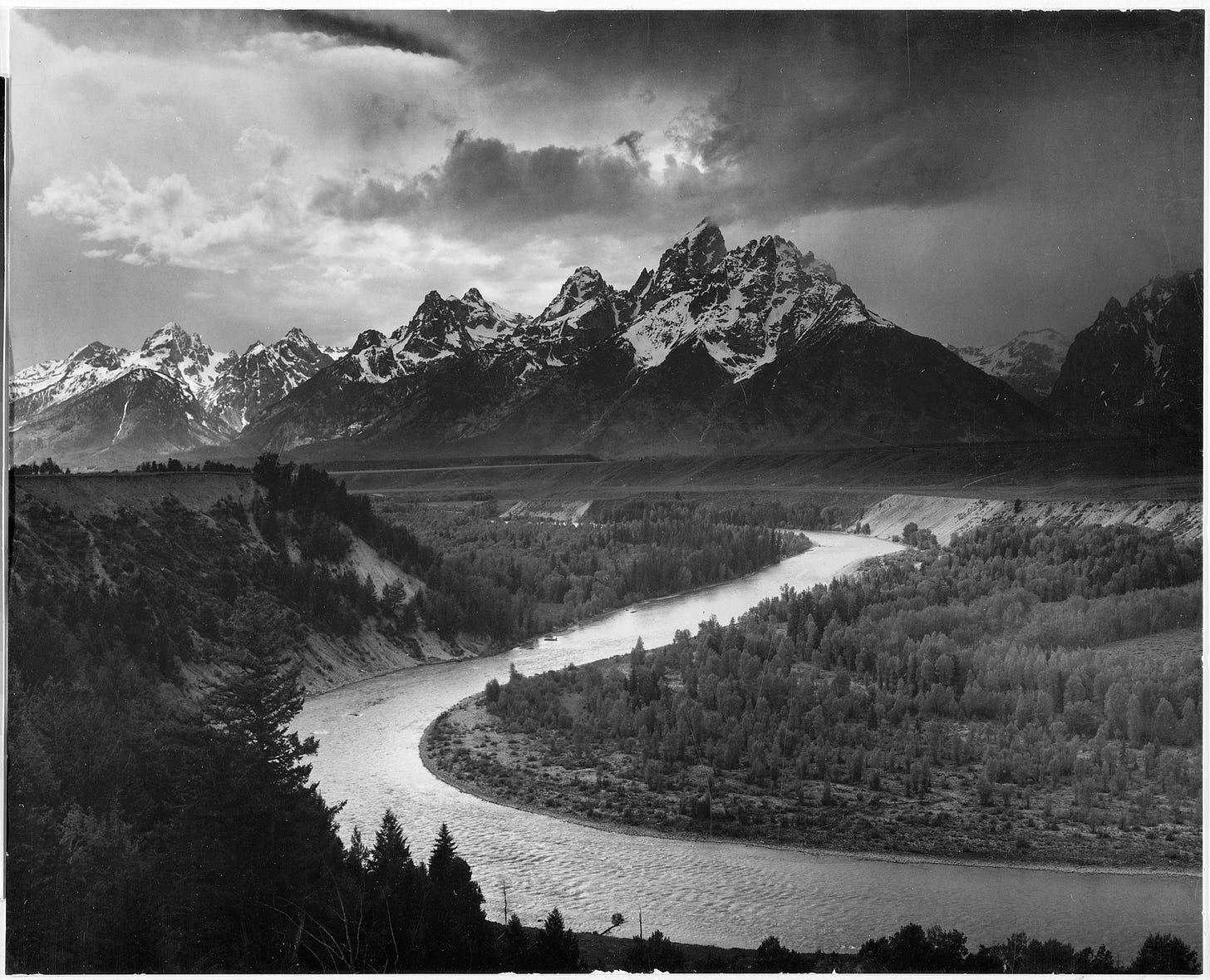

In the summer of 1941, at the age of 39, Adams was recruited by the United States Department of the Interior. His assignment was simple: travel the country making photographs and, for up to 180 days in the coming year, photograph national parks and notable American landscapes at a rate of $22.22 per day. That would amount to $4,000, triple the average annual household income at the time. The government would provide all film, paper and chemistry, and in return Adams’ negatives would become its property—public property—for use in the creation of murals.

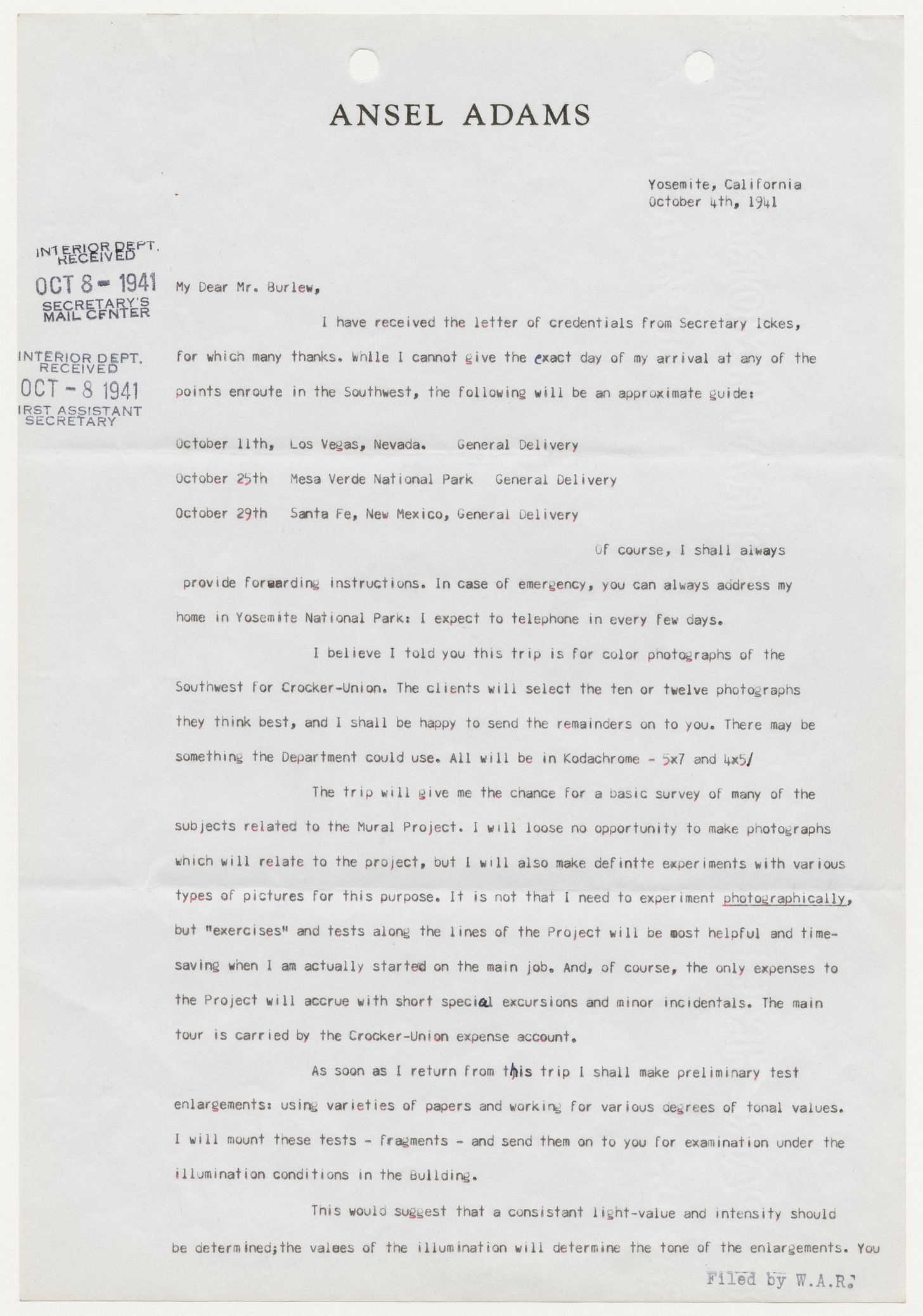

When Interior Secretary Harold Ickes began commissioning artwork for the halls of his new office building, he decided to augment the painted murals with photographs. After initially cryptic correspondence, First Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior E.K. Burlew explained to Adams that Secretary Ickes would like to commission 36 mural prints. Adams accepted the offer on October 14, 1941 and was appointed to his post: Photographic Muralist, Grade FCS-19.

Project details were ironed out by postal service and telegram, and much of that correspondence is contained in the same file at the National Archives and Records Administration as the prints Adams ultimately produced. The letters provide a fascinating insight into the photographer, his demeanor, and his plans.

In an October 4 letter to Burlew, Adams details his travel plans for the coming weeks, explaining that although he will be working for two other clients, he would seize every opportunity to make photographs relating to the mural project on a trip through the Southwest. In an effort to continue their correspondence, Adams went on to explain that he could be reached by general postal delivery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on or around October 29. He didn’t know it yet, but he was describing the time and place in which he would produce one of the most iconic landscape photographs of all time.

Three days later, on November 1, 1941, after spending the day fruitlessly photographing near Santa Fe, Adams was returning to his hotel in the late afternoon when a glow in the fading light caught his eye. He quickly pulled his car to the shoulder of Route 84 and hurried to capture a frame in the twilight. At precisely 4:49pm, he opened the shutter and made a single exposure, but it was enough. It depicted the moon rising over the village of Hernandez, New Mexico.

Though on assignment for two commercial clients and the U.S. government, the now famous moonrise image was made for Adams himself. In subsequent correspondence with Burlew, Adams made clear not only that he would use government film for the mural project and his own film for personal work, but also that he took no issue with the government’s outright ownership of the copyrights to images created for its murals.

“I am quite certain that no problem will arise about government ownership of the negatives,” Adams wrote. “The pictures will be made for an especial purpose—the Murals—and, while they may have some publicity value to your department, they should not be used otherwise. If I come across exciting material that I would want for personal use I will photograph it on my personal film. It will be a simple matter to keep material accounts straight. Conversely, when I am on personal excursions, I will not neglect opportunities to make negatives for the project.”

“In these matters I shall be reasonable,” Adams continued. “The details will work out as we go along.” The tenor of his letters is magnanimous. Time and again, the photographer offers to go above and beyond what was required of his assignment, to accommodate any alterations his employers might request, and even to go so far as to work beyond the 180-day contracted maximum without pay in order to complete the project as the artist envisioned it.

Adams designed the murals project to have one major subject on which he would concentrate, as well as two secondary subjects. His principal focus would be the national parks, a series he hoped to complete by June 30, 1942. The secondary subjects would be Native American arts and crafts, and the Native American lifestyle in general. In each case, these subjects were important to Adams throughout his life.

In yet another letter, Adams made clear that he had no intention of creating the kind of dark, depressing documentary images that came out of Depression-era Works Progress Administration assignments.

“The treatment I propose for the above subjects would in no way be reminiscent of the documentary photography of the 1930s,” he wrote, “in which a more or less negative aspect of our civilization was stressed for purposes of social improvement and reform. I would stress the positive aspects; the advancement of civilization and the grandeur of our natural environment.”

Two months after the commission began, the attack on Pearl Harbor ushered the United States into World War II and Adams wrote to Assistant Secretary Burlew again, this time to offer his talents to the war effort in any way the bureaucrat saw fit.

“May I assure you of my eagerness to be of service in every possible way at this time,” Adams wrote. “I trust you will not hesitate to request my services in any way consistent with my abilities. I believe my work relates most efficiently to an emotional presentation of ‘what we are fighting for,’ but if the need should arise I will gladly undertake any type of work required.”

Fully expecting to join the Army or Navy in a photographic capacity by the end of 1942, Adams grew increasingly eager to complete his mural project as soon as possible. He had photographed nearly a dozen national parks and monuments, and eventually would deliver 221 gelatin silver prints to the Department of the Interior. With the focus on the war, however, Adams’ appointment was terminated in July of 1942 and the murals project stalled—until 68 years later when in the spring of 2010, then-Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar commissioned 26 mural prints of Adams’ images from the project to be displayed on the first and second floors of the main Interior office building. It took a lifetime, and Adams himself never got to see it, but his government mural project was finally complete.

Because Adams produced the photographs as a government employee, he didn’t retain their copyright. The U.S. government holds full rights to the images, though Adams did ultimately keep the negatives. The images are in the public domain, free for use by the American people however we may see fit. All because, for a couple of months in 1941, Ansel Adams got a government job.

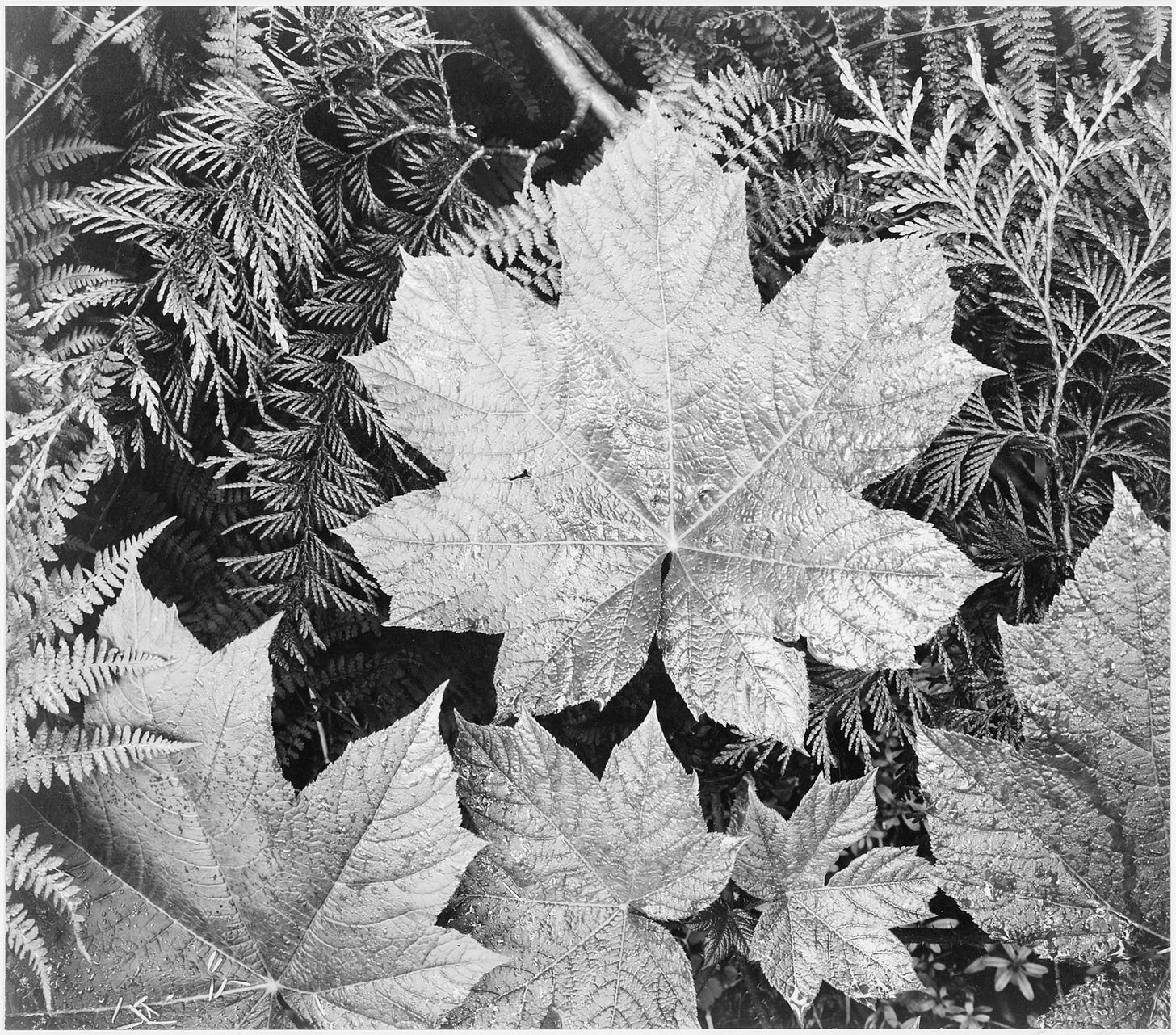

For more information on Ansel Adams and his government mural project, visit https://www.archives.gov/research/ansel-adams. A modified version of this story first appeared in Outdoor Photographer magazine. All images courtesy of the National Archives.

A wonderful read!