The Unguarded Moment

Steve McCurry takes a personal approach to photographing people around the world

When Outdoor Photographer magazine folded, hundreds of features and profiles disappeared. In an effort to preserve this work, I am reposting some pieces here at Art + Math. The following interview was originally published in Outdoor Photographer in March 2010. Text by Bill Sawalich, photographs by Steve McCurry.

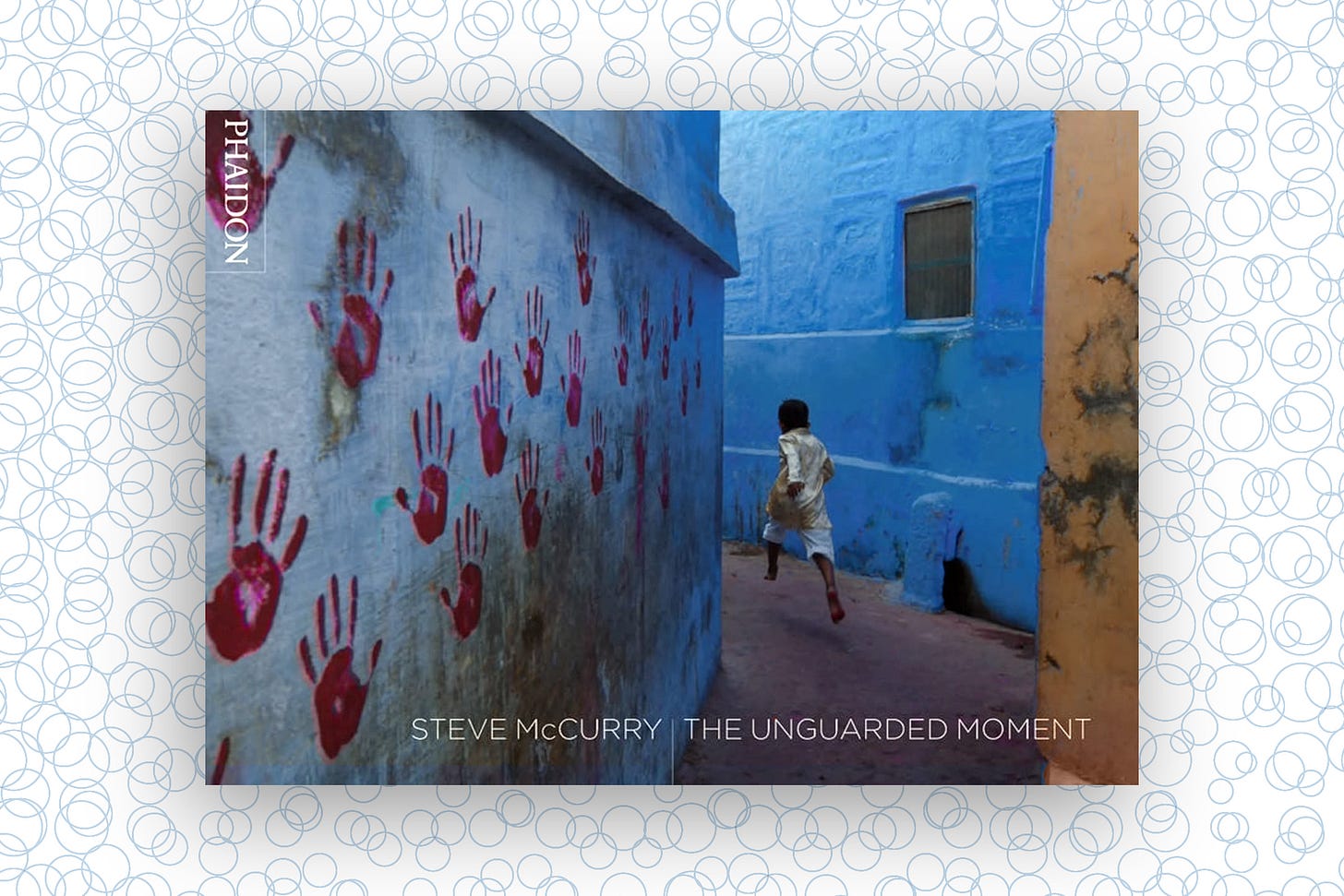

It’s obvious at a glance that the cover of Steve McCurry’s new book, The Unguarded Moment (Phaidon), is a great photograph. The more you look at it, though, the more it draws you in. You study it, wondering about the running boy caught midstride, midair. Where is he going? Why is he running? You consider the life he may lead, how he came to live in such a place. You shift your gaze to the handprints on the wall. Who put them there? Are they entirely innocent or slightly sinister? The scene is unquestionably beautiful, but it raises as many questions as it answers. The moment is pure tension, a coiled spring, a consequence of the decisive moment.

McCurry’s photographs, often portraits that center on people in the mundanity of their daily lives, tend to feel like the kind of images Henri Cartier-Bresson, pioneer of the “decisive moment,” would have produced had he worked in color. Perhaps that’s the most appropriate way to think about McCurry’s work, too: built on photography’s inherent ability to capture moments like the cover of his book.

“I’ve been in that town many times,” McCurry says of the image from Jodhpur, India, “and I know it very well. That particular street, that alleyway—I recognized all those hands on the wall, and there was a sort of simplicity to the design. It was a very busy alleyway. There were cows and women and workers and people with bicycles and motorcycles coming through that alleyway. I took a number of pictures, many of which are fine. It’s just a question of working and waiting for something to come into your frame that will complete the picture.”

If he makes it sound simple, it’s because, to McCurry, the process is inherently so. He seeks simplicity in every aspect of his photography—from the equipment to the technique to the way he finds and engages with his subjects. Simplicity may be his guiding principle, second only perhaps to human interaction and interpersonal connection.

“When you’re out shooting, it’s not just about the pictures,” McCurry says. “It’s also about enjoying your afternoon, or the people you’re photographing, the places you’re photographing. A lot of times when I’m walking down the street, I’ll talk to people—maybe this seems so obvious—I’ll talk to people that don’t even have anything to do with photography. You’re out trying to experience the place. I guess it’s so fundamental, so basic, but I notice sometimes that gets overlooked. For me, photography is more about wandering and exploring, human stories, unusual serendipitous moments that make some interesting comment about life on this planet.”

McCurry frequently refers to his photographic role as that of the wanderer. While his images represent a perfect storm of composition, lighting, color, human emotion, decisive moment and perhaps any number of additional intangible qualities, he says he’s not particularly conscious of them. His focus is much simpler.

“I think my brain is sort of thinking of these different elements simultaneously,” he says, “but the one that’s at the forefront, the one that’s most important to me is the story or the human element or some emotional component that may make some comment on the human condition. We’re all human; we’re all in this experience together. We kind of want to share our experience and compare it to other people. When you’re photographing something that’s purely about design, what’s that about?”

Deliberately eschewing precious style in favor of creating personal connections, simplicity of approach becomes as much a tool as any camera technique might be. For McCurry, obvious technique clouds a successful image rather than enhancing it.

“I’m trying to get beyond some clever artifice,” he explains, “a particular way of printing or black-and-white or the tilt of the camera or something where you think, ‘Well, that’s kind of cool,’ but there’s no substance, it’s totally style. I try and work in a way that’s more about the soul of something. It’s not flashy and gaudy or overproduced. It’s just something simple, something minimal.

“I think it’s important not to draw attention to one’s technique and let the picture speak for itself,” McCurry continues. “Let the viewer get absorbed in the emotion or the story that you’re trying to tell. As soon as you start thinking about the particular lens, particular filter or some clever lighting technique, it takes the attention away from the picture. I’ve never been really interested in the technical side of, well, of anything for that matter, but particularly photography. I know enough about the camera, I know enough about the craft to do my work, but it’s not something I really dwell on. I use a simple camera and a couple of lenses. To light things and all that nonsense, that becomes more like work. Whereas when you’re just working with the light, working with what you have, then it becomes a lot more fun. And I think you get a better sense of life.”

“Photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson and André Kertész would only use one or two lenses and work mostly in available light,” he says. “I think the simplicity creates this timeless quality. There’s a freshness, an offhanded quality to it.”

McCurry works primarily with ambient light and he says more than 90 percent of his pictures are made with prime lenses—the 35mm and 50mm especially, although he shoots with zoom lenses now. Technical minimalism is something he doesn’t often see from other photographers, particularly those in his workshops. Students forget the basics of simple equipment, simple technique and simple humanity that are the foundation of McCurry’s entire body of work.

“With students, now and then,” he says, “it’s more about the photography when it should be more about experiencing life and observing. They have all this equipment and they’re trying to take everything they can possibly carry so there’s not anything that can get past their lens. It’s almost a burden. I was out with some people, and they kind of raced up to this person and started clicking and they didn’t say hello. They didn’t say hello, they didn’t say goodbye, there wasn’t any kind of communication or niceties.”

It’s the basic human interaction, the spirit of a pleasant afternoon spent exploring, that really enables McCurry to make the connections he seeks to photograph. These skills, not camera skills, per se, allow him to distill his unguarded moments. He insists a practically leisurely approach is paramount.

“I think you do your best work when you’re in a particular frame of mind,” he says. “If you’re out taking a walk, a leisurely walk, a walk where you aren’t really going anywhere, you’re just kind of there in the moment and appreciating that particular unique city. Maybe as a traveler. As a pilgrim. An explorer. You’re just out. That’s the kind of space you want to be in. You have to be childlike in your fascination or in your curiosity or in your playfulness with things around you and people around you.”

“One critical element of all this,” McCurry adds, “is you have to engage your surroundings. As you move through the situation, as you move through those streets of Jodhpur, you have to engage—the people, a dog or a cat or a cow or a child. I think you have to interact with these things and stop and talk with somebody or play with somebody. That’s really important because then you’re inside of your surroundings, you’re inside the situation, you’re not an observer, you’re not on the outside looking in. You’re in it. When you’re inside of it, you’re not separate. You’re one with the thing, with that place. And a lot of it has to do with interacting with the situation.”

“Clearly, I’m a foreigner,” he continues. “I might be a foreigner, but I’m still a human and I’m still playful with people, and that commonality can be the point. I’m dressed in a particular way, you’re dressed in a particular way, we don’t speak the same language, but we actually have more in common just because we don’t speak each other’s language. If I come up and put my arm around you and make a joke, you’re going to laugh, and suddenly we’re sharing a moment, even if we don’t understand the language. Then you have that kind of bond, that connectedness.”

McCurry’s wandering approach is fundamental, but on assignment for National Geographic his time on location is finite. These two pressing issues are in direct opposition, which can make settling into the appropriate frame of mind a challenge. It’s made even more complicated because success requires, as much as anything, the patience to wait, or the discipline to return later to find the perfect moment.

“When you’re on assignment but you do have time constraints,” he explains, “you just have to try to relax. If you’re out shooting from early morning until the sun goes down, you can’t do better than that. Nobody can. You’re seeking out situations and places and light that are going to work for your pictures. You intentionally go to a particular location based in large part on the light; a lot of your routine is based on those kinds of variables. And when you’re wandering around, you can see one thing and decide, well, the light’s not right, the moment’s not right, whatever, and you can continue walking down the street and find another situation.

“There are times when you go back five, 10, 15, 20 times to the same street or the same location,” McCurry continues, “because you’re seeking something out, you’re looking for something or waiting for something to happen. Every day, there’s different light and you’re in a different mood, it rains, it’s sunny, your frame of mind is different, so you go back, and magically things happen. And sometimes they don’t. But you go back.”

The place to which McCurry has continually returned more than any other throughout his career is Asia. India, in particular. The vibrancy, the ornament, the people, all are a draw to the photographer who wants nothing more than to explore and experience. India has continually provided the ideal subject.

“India has been one of the most important places that I’ve worked and photographed over the past 30 years,” he says. “It was the first country that I traveled to as a young photographer, and I found it so unique with its varied cultures and customs and regions. The mix of Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Islam, Christianity—and to see how they all intermingled—was a constant source of fascination. I was in Ladakh, India, recently living with some nomadic shepherds. I was struck by how little their life had changed. With the exception of some solar panels to create light and their Jeeps parked next to their tent, life seemed the same as it may have been hundreds of years ago.”

Being able to travel the world and explore exotic locales, interacting with a diversity of people and cultures, seems to be at the root of McCurry’s motivation. The camera is the vehicle that has allowed him to lead such an enriching life, and his appreciative approach is one from which he suggests many photographers could benefit.

“I think what keeps you motivated and keeps you going,” he says, “what sustains you… The idea is to enjoy your life, to be fascinated, to be curious, to experience the world and learn. To have it be all these things.”

The Importance Of Color

Looking at The Unguarded Moment, it’s clear that color is important in Steve McCurry’s work. Just how important, though, is up for debate. “Like Cartier-Bresson in color,” is how he describes it, assuming that color was at the forefront of his photographic approach.

“I never really think of color when I’m working,” McCurry clarifies. “That’s not my primary interest. Often, I don’t think too much about the use of color other than trying to avoid a color palette that may be distracting or garish. Of course, I notice colors and how they fit together, but I don’t really consciously go out to make color photographs. Obviously, there are times when you’re confronted with a situation that has a strong color component and, of course, you work with that, but it’s not my main motivation. There’s something I’m trying to distill down to, some essence. I’m trying to get a certain balance that’s not about the color.”

Though his work isn’t about color, McCurry doesn’t ignore it. In fact, he seeks situations with particular tonalities and he deals with them deliberately—as long as the image doesn’t become about color.

“When you’re cruising around, you can’t control what colors are out there,” he says, “but you can control what you photograph. For me, color photography works best in muted, soft-lighting situations with low contrast. I gravitate toward low-light situations. Dark, cloudy days are my favorite situation to shoot in. I get the best results from muted, low-contrast, even light. My eyes are extremely sensitive to light anyway, and with or without a camera, I don’t really enjoy walking around on a bright, sunny day. I much prefer, even without a camera, a cloudy day.

“It was the vibrant color of Asia that taught me to write in light,” McCurry adds. “Still, color alone, or structure for structure’s sake, are not, for me, what finally make a good picture. What makes a powerful image—much like Asia itself—is the confluence of all these elements. More than 20 years later, I still keep shooting in Asia because the place—like the light and the belief that powers life—is inexhaustible.”