Paper Trail

My love letter to an obsolete technology

Another print publication died today. It’s just a local thing, but fairly vibrant (or so it seemed) and approaching two decades in print. I’m sad to see it go. Unfortunately I’m getting used to it.

I really liked newspapers and magazines. I still subscribe to a handful, but I will confess that they often linger unread for too long. It’s because I reach for my phone instead. I may love print but I’m part of the problem. Even people who love print don’t love it like they used to.

I’d rather read a book than a screen. I like to take notes using a pen and notepad. I want to read your zine but I don’t care about your blog.1

There is a tangible, tactile nature to paper that’s missing from digital life, and I’m not happy about it.

Paper is a commitment. There is a cost to paper and ink. The mere act of printing itself is an endorsement: “This is worth reading. You can tell because we spent money to make it.”2

We think differently when paper is involved. My first big boy job was copy editor at a publishing company. They’d hand me galleys, on paper, to read and mark up. Everything was laid out in the computer, but when it came to reading, the standard operating procedure was to print first. It engages the brain in a meaningfully different way, or so we were told. (It’s true.) Judging by how things have been going in our digital society, I’d say the anecdotal evidence supports it.

I like paper because it manifests in the physical plane of existence. I can crumple it up or light it on fire or chew it and swallow it. It’s not ephemeral, like this document I am writing now, in my car, on my laptop, stored in a cloud.

I even like boring paper. I like doubled-up Post-It notes and dog-eared scratch pads and repurposed file folders and sauce-stained cookbooks. I like the optimistic anticipation of empty Field Notes and Moleskines. I like yellow legal pads with just a few pages remaining. I like old cardboard and new cover stock. I like signs; bonus points if they’re hand lettered. I like adding stickers for whimsy. I like holding stuff together with tape.3

I like concert tickets and bookmarks. I like cash instead of card. I like boarding passes and photo books. I like gift certificates, not gift cards. I like the commitment of paper. It has weight. We could use a little more of that kind of seriousness in our lives. Far fewer hare-brained terrible ideas are shared in print than online, I’m certain. Because paper requires commitment.

I don’t believe I am expressing a luddite’s appreciation for paper (though that, too, is pretty well documented). This is but a broken hearted memory of all that we lost when paper ceased being important.

In 1984 I made my first darkroom print at summer school, age 9. I recall the picture very well, and I’m sure it still exists in the recesses of my parents’ basement. It was a borderless 8x10 and I watched it emerge in the developer under red light. It depicted the playground at Signal Hill school. It was — you’ll have to trust me on this — a sublime work of devastating genius.

Paper was instrumental not only in my first forays into photography but throughout the entirety of my education that followed. I loved the slick gloss of RC prints made in the high school darkroom. College taught me that if I wanted my art taken seriously I’d better switch to fiber based paper. My preferred brand was Oriental Seagull — what a name! — though as I matured I would dabble with others, convinced that the right paper would catapult me to fame and fortune. The last paper from my darkroom era, which ended about 20 years ago, was Bergger Prestige. I learned of it from Rolfe Horn, still a favorite of mine and a protege of Michael Kenna. If it was good enough for him, I figured, I should be able to make do. Some of the last serious darkroom printing I did involved the infectious development method of lith printing, channeling my inner Anton Corbijn in the process.

Looking at them now brings me back to exactly why I loved paper. Not only are these images a pale reflection of the actual prints, but the digital version simply can’t recreate this analog process in the same way. It’s missing the chemical magic. It can get close, sure, but the devil’s in the details.

Toward the end of my analog era I spent less and less time in the darkroom — a few times a week became a few times a month and then a few times a year and next thing you know I’d stopped. Goodbye dark rooms, hello bright screens.

The real travesty was selling it — a full professional darkroom complete with enlarger, filters, filed negative carriers, trays, tongs, thermometers, beakers, funnels, timers, safe-lights… A truckload of equipment. Literally everything for a darkroom but the water. After weeks of its listing eliciting zero calls, one person finally reached out. He offered $200 for everything.

If this were a personal finance newsletter I’d refer to this as “selling at the bottom” because soon enough darkroom use was back on the rise. Now it’s a charming process that some photographers still enjoy. Well, they shoot film at least — who knows how much they enjoy it. Apparently just doing it is enough to pass for a personality.

I didn’t set out to write today about chemistry and film, or the lost art of the darkroom. I just want to talk about paper. Because I loved it once. I mean really loved it for so many things. And it’s just not in my life any more.

Once the darkroom went away I made inkjet prints. Oops, I mean giclée. That’s what we were calling it back then in hopes someone would pay $800 for a computer printout if it had a French name. As I recall, the last time I printed anything that mattered would have been 2021, the single post-COVID semester in which I still taught a college photography class. Something about the lockdown broke the college system, or the students, or me, or all of it. So I ceased teaching (a genuine travesty) and have not yet resumed. The only meaningful outlet I had for making prints is gone.

My clients long ago stopped needing prints. I’m just barely old enough to remember when a grip-n-grin or headshot was delivered as a black and white 5x7 on RC paper. But those dwindled over the years as digital files became preferable so now, in a digital world, I simply don’t need to print my work.

But I want to.

I know I could make prints. I should make prints, absolutely. But I don’t. That’s the sad fact. Which brings me to the point: You can be a professional photographer in 2025, taking pictures every day, and never see your work on paper. What a travesty.

In the good ol’ days, paper was an essential part of the photographic process. Hit your local antique mall and you’re sure to find a dollar box filled with cabinet cards and cartes de visite. And these plain old portraits are more interesting than ever, just by virtue of surviving. Which they did because they were printed on paper.

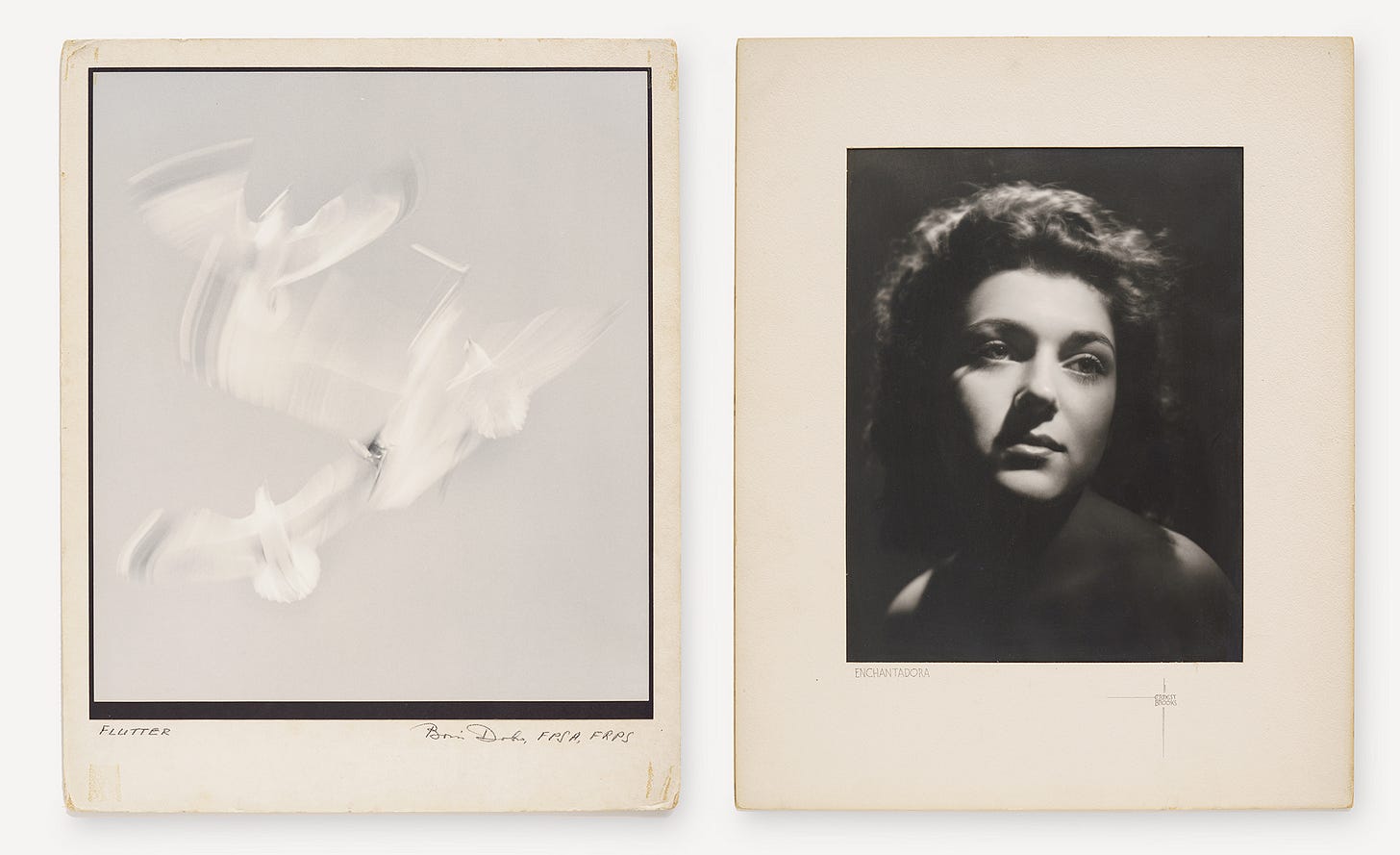

I once rescued a batch of beautiful prints from the garbage. I was in grad school in the late 90s, working for the facilities crew mowing lawns and patching drywall. One day I opened a dumpster to find that a professor must have cleaned out his office and discarded several matted 11x14 prints. I can’t imagine what he was thinking because I dusted them off to discover a treasure trove of some minor importance: prints by esteemed photographer and longtime instructor Boris Dobro as well as the school’s founder, Ernest Brooks.

We didn’t always respect it because paper was everywhere. But just by virtue of existing in the physical plane, it allows one man’s trash to become another’s treasure.

Film sales peaked in 2000, then declined fairly rapidly for eight years before disappearing completely around the time the iPhone arrived. It wasn’t so much the switch to digital cameras that killed paper, it was the social media revolution. The first generation of digital photographers made prints, and presumably some of y’all still do. Artists continue making prints, thank goodness, else we’d be talking a lot more about NFTs. But I think a lot of people now see the end goal of their pictures as a screen — shared on social media via the cloud rather than in person on paper.

Have you noticed that the signal to noise ratio is out of whack? It’s because any dummy, your intrepid author included, can broadcast to the masses without spilling a single drop of ink. So everyone’s doing it, and the genius stuff like this is all mixed in with the terrible stuff that’s vastly more popular. Not that I’m bitter.

As photographers and writers and creators of all kinds left the paper world behind, it’s become harder and harder to tell what’s worth consuming. Well sure, easier in the sense that you can get it anywhere via your computer or tablet or phone, and I can reach an audience around the world for a total cost of zero dollars. But that reach and convenience comes with a cost: there’s not much need for paper any more. Which stinks because paper is such wonderful technology.

I took a bookmaking class in college, taught by photography professor Beth Linn, and it was fantastic. We went on a field trip to a beautiful little paper store in Chicago where we bought huge sheets of gorgeous handmade Japanese papers for use in our books and boxes. I still remember the store, though I don’t remember its name, and I’m holding out hope it’s still there, sitting happily under the L.4

Before that trip I’d never truly considered just how beautiful paper could be. It is the stuff of literature, the stuff of art.

I’m going to try to resume printing my work, for a number of reasons. Not the least of which being that I want it to last. I’ve spent my career making pictures, and for the most part, the work I do on a daily basis resides on clouds and websites and hard drives. When I go, it will too. I don’t like that idea at all. So in an effort to give my work — both words and pictures — some staying power, I’d like to start printing it. I would like for my life’s work to stick around awhile. In the digital world, nothing sticks around at all. This is a problem paper is uniquely suited to solve.

I want my kids to occasionally put down their phones and instead look at the pictures of our family, from when they were little, from when I was little, from when their ancestors were little. I recall thumbing through photo albums as a kid, seeing how important those printed pictures were. Using them as a direct means of connection with family I’d never met, or with those who I’d known too briefly. I want my kids to have that. I want you and your families to have that too.

Do you ever find an old note, from a grandparent perhaps, or an old friend, or your younger self? Maybe it was a love letter, or maybe it was a lunch order, or maybe it was just a phone number scribbled on the back of a church bulletin. I want these artifacts. I want that little connection with the past, with my lost loved ones, popping up one random day far in the future. I need paper for that.

I’m going to make an effort to embrace paper, strategically. It does some things no amount of pixels or processing power ever could. The right tool for the job, that’s what they say. I think the right tool for a lot of things has been with us the whole time. Fragile as it may be, paper makes things — ideas, people, memories — paper makes them real.

What can I say, I’m a hypocrite.

Note that Art + Math is only available online. For now.

I really like tape. As a kid my parents had to ask me to stop using so much of it. I don’t know which came first, my love of paper or my love of tape.

The proprietress had the most beautiful handwriting I’ve ever seen. She printed with the accuracy of a machine, and even her invoice was a thing of beauty. I suppose if your career is in paper, you want to do it justice when you put your hand to it.

We have forgotten. It is a great shame. I ran into a kid not long ago who could not read the note I had left him because it was written in longhand. Legible longhand, I might add. I found a note from my father not long ago in a box, as I was reorganising. He wrote in a very fast, fluid and a little bit expressive way, which I never did. Paper is important. We cannot lose it. Get back in the darkroom. Make some of those fancy-French-word inkjet prints. Really good post! Thank you.

Before I was photographer, I was a writer. No, not as a pro but as a strength, a native skill that developed over time from academics and literature to business and community work.. The most important use was as supporting my personal journals.

At one point the actual putting of ink on the page was so tactile that I progressed to fountain pens and heavy paper stock and put, put, put words on paper; elaborating the contents of my brain. By that it became fact, illusive just in my head but once put there on the page, something to consider and rethink. I made things real.

Maria Montessori was a serious devotee of the use of tactility for learning. Computers don't have that. We may simply experience the sense of tangibility differently than our online friends. And, it may be that the tactile sense, even mechanically, is directly hooked up to us by our fingers and hands, those parts of us that make us unique on our planet. I wonder that punching keys does the same thing.

Now, I dump ideas onto the screen and soon see a flow. Eliminating similar phrases or duplications and meld them into one good sentence. Copy and pasting content from one area into another. It works fine for business and academics

However, this is after "mastering" the language on paper. It may be that my mind is simply not as dynamic as it was at 23. But what was there then, and its method, is internalized after countless thousands of hours of writing. So much foundation had been built and has stayed with me. I can make it happen on the screen.

It may be that our bright young writers get their ideas out and onto the page with a keyboard or touchpad. That method, the process of thought emerging, unlike handling clay or a tool, is not an extension of our organic physicality expressing point, place, and ideas on substances we can feel and control. That is missing.

So what? Stay tuned.