Maisel’s Bank

On the power of a place to live the photographer’s life.

I recently wrote about how I don’t covet camera gear. That’s mostly true, although Leicas do hold a special place in my dreams. And I will admit to an embarrassingly large collection of bags and cases, which speaks to my affinity for organization as well as a fear of commitment. In my ranting about “missing the point” and “camera-ists” and such, I neglected to mention one of my deepest, longest-lasting photographic obsessions: I lust after studios.

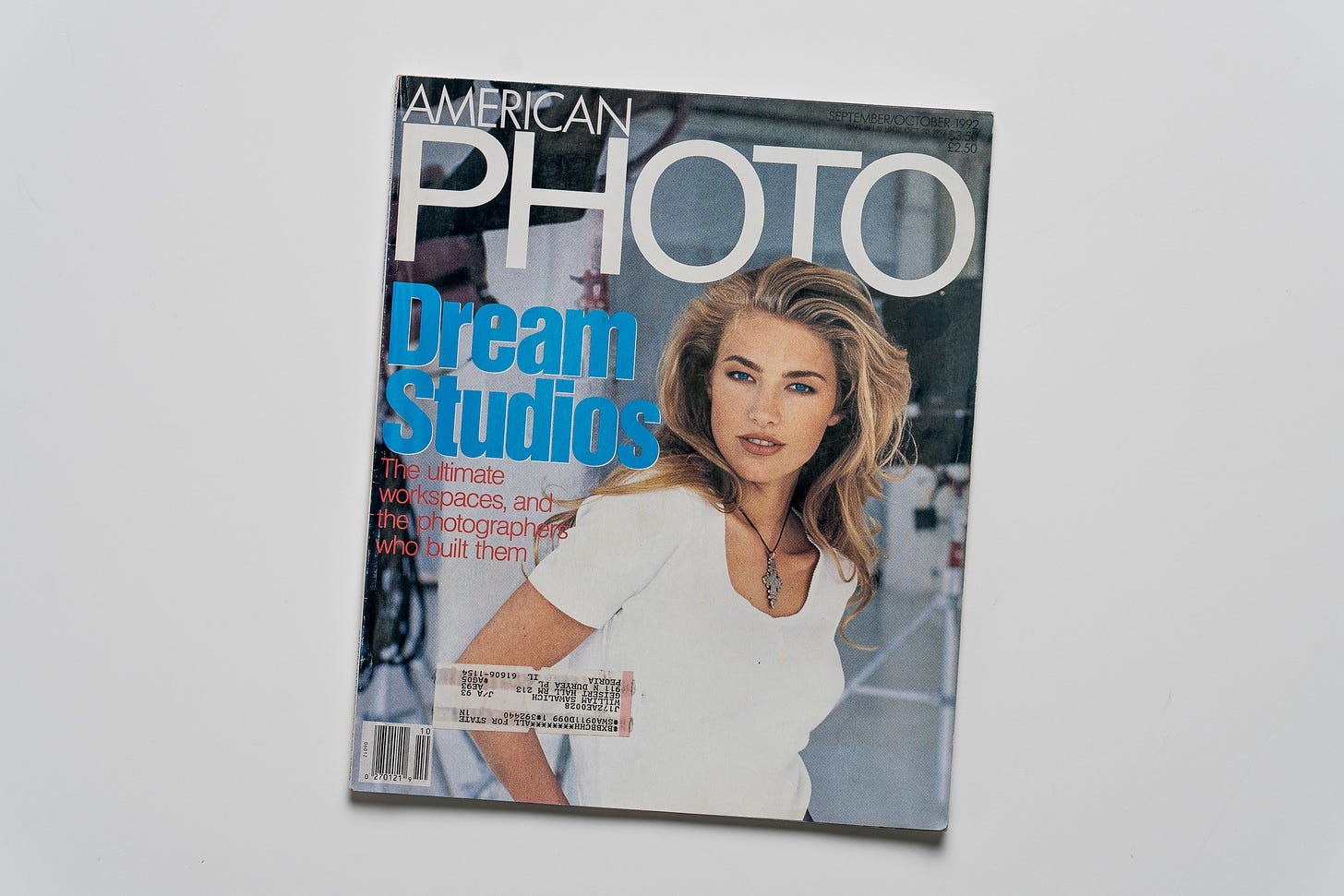

It all started way back In 1992 when I, as a fetus, picked up the September issue of American Photo magazine. It featured a cover story about dream studios and the photographers who inhabit them. It profiled ten photographers and their unbelievable workspaces. It managed to showcase a car studio in Detroit, a converted Kansas City firehouse, a Southern California skylit space and two converted 19th century banks in New York City.

One of those banks is an allegory worth exploring.

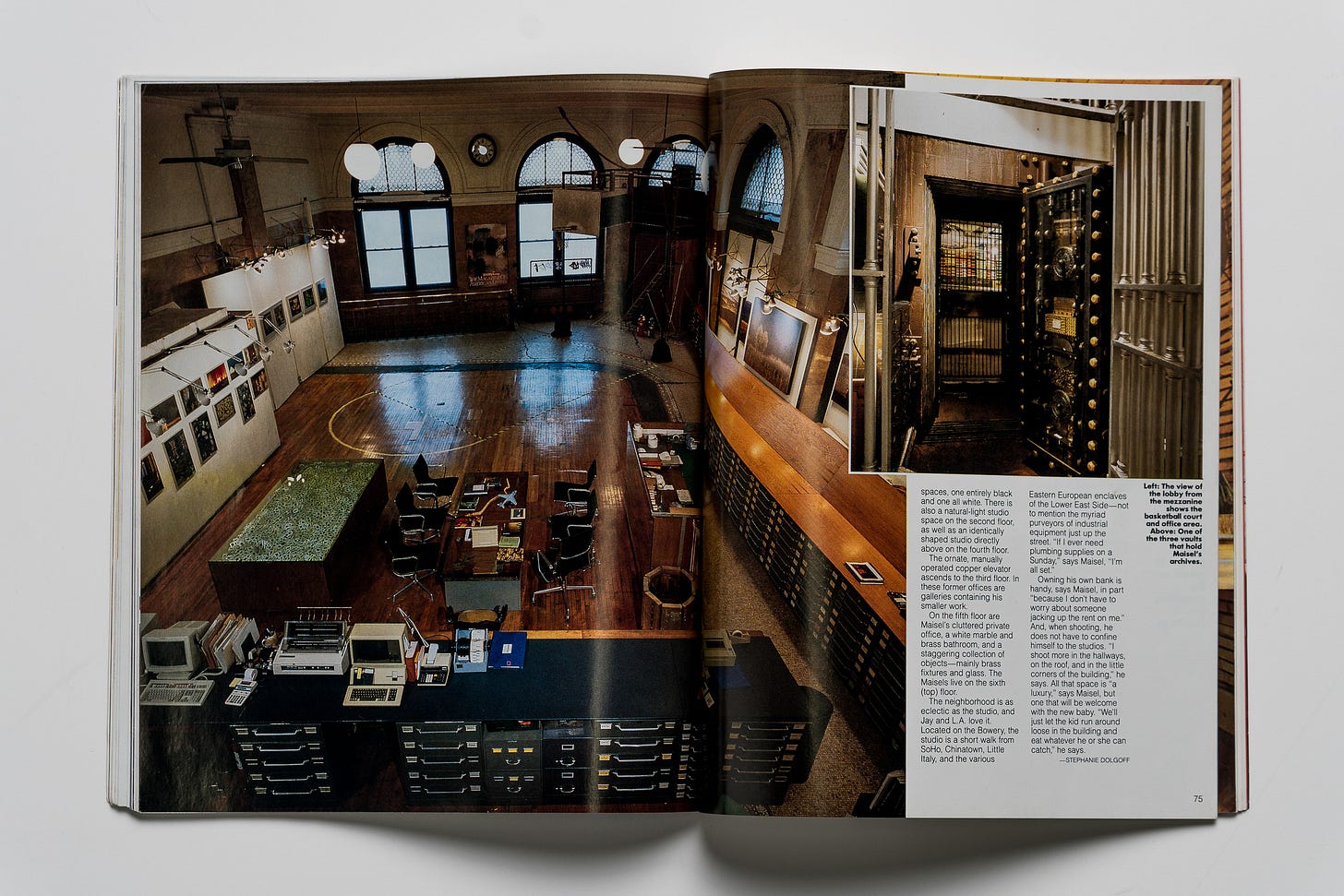

In 1966, young Jay Maisel bought a six-story bank at the corner of Bowery and Spring in Lower Manhattan. He paid just $102,000 for the 72-room, 35,000-square-foot building in what was at the time a rough neighborhood getting rougher. The area has, shall we say, improved—to the tune of $55 million. That is the sum for which Maisel sold his bank/studio/home in 2018. At the time it was the largest individual real estate sale in New York history. A good gig if you can get it.

For 49 years, Maisel, his wife and their daughter lived on the upper floors of the bank—which was graffiti-covered and mysterious to neighbors who assumed the property was abandoned—while he used the lower floors as a combination office, studio and archive. The 1992 American Photo article showcased a feature of Maisel’s studio that stayed with me all these years: a fully functional basketball court, where the photographer could shoot hoops at leisure.

It was the coolest thing I had ever seen. Reason enough to become a photographer, I thought, with hopes of one day converting my own former bank into a combination home and photo studio complete with a working basketball court. It’s a common dream.

While I have officially abandoned any hope of my own lower Manhattan converted bank basketball studio house, I still harbor dreams of that type of workspace—the effortlessly cool, inherently interesting and beautiful space where a photographer can live, work and play, all at the same time. As the editors of American Photo wrote 31 years ago: One of the perks of being a photographer is working (and sometimes living) in a wonderful space that fires the imagination… These dream studios are elegant evidence that photography is not only a job, it is a way of living.

Amen! The studio—particularly the live/work variety—is the ultimate manifestation of photography as a way of living.

But my informal survey tells me that studios are becoming increasingly rare as they become less necessary. In 1992, a photographer who wanted total lighting control needed a studio in which to work. But with the advent of low-noise and high dynamic range digital sensors, the need for complete lighting control was eliminated. These new technological capabilities met in a perfect storm with a change in aesthetics spurred on by Instagram, which took commercial photography away from studio sterility and out into the authentic real world. Art directors began to prefer imperfect reality to the polished precision of a studio, so studios became less necessary.

Still, I covet.

Along with the freeing, downright empowering nature of a dedicated workspace, there are business benefits as well. A studio can be rented to other photographers with a periodic need, providing an additional revenue stream. And that revenue stream can be particularly helpful in tough times, when the studio also provides the artist cover for working one’s way out of creative or economic doldrums.

Others counter, though, doldrums are precisely the reason not to be burdened by a studio—particularly an expensive one. Maisel sold his bank not because he was ready to retire upstate, but rather because the $300,000 in annual upkeep was becoming a bit much.

I suppose a studio’s efficacy is largely dependent on the kind of photographs one makes. If you’re the next Penn or Avedon, a studio is surely helpful. Or for shooting products, fashion, or fine art still life, a studio is a necessity. But all manner of photographers, from journalists to lifestyle photographers, may have no need for such a space. It’s either a good investment or a bad one, depending on the use case (and whether it’s 1966 in lower Manhattan).

An interior designer once told me his most fundamental business advice was to own your own workspace, because no matter what went on with your business you had an asset of inherent value that could be rented for revenue in a pinch. It can also provide a safe haven to keep working during turbulent times. A refuge of sorts.

Not more than a few days after receiving that advice, though, another entrepreneur shared with me their secret to success: Never own your own space. You don’t want to be burdened by this expensive albatross around your neck! How will you pay your mortgage in a bad economy? Instead it’s much better to stay nimble and navigate whatever turns up, renting space as needed and happily working on location when it’s not.

So I don’t know if I can make the ultimate business case for a studio, much less one of the “dream” variety, but I can certainly make a creative case for one. You need a place to work, to practice, to experiment risk-free.

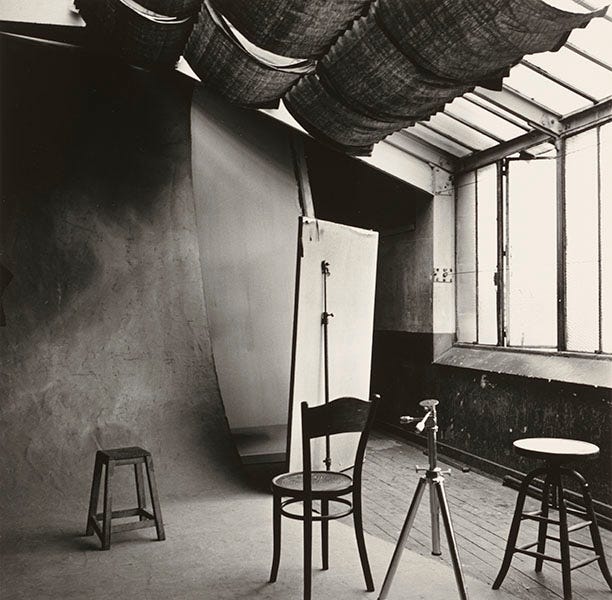

What does a studio need? My personal short list would include high ceilings and natural light. I’d love to have one of those 19th century north light windows you see in old Parisian lofts, or early metropolitan portrait studios. And a lot of open space, room to work unencumbered. The first thing I do on location, after all, is clear all the stuff out. In the immortal words of Helmut Newton, photography is 10% inspiration and 90% moving furniture.

What does a dream studio look like? Jay Maisel filled his with the oddities and tchotchkes that piqued his interest and stoked his creativity. Dan Winters takes a similar tack in his Texas studio.

Winters’ Austin workspace aside, it’s no surprise that many notable studios are in the photography capital of the U.S. If you’re in the market and Maisel’s bank is out of reach, consider Weimaraner photographer extraordinaire William Wegman’s beautiful Chelsea home and studio. It went up for sale last month with an asking price of $16.5 million—a deal in the context of Maisel’s big bank.

I recall once seeing a real estate listing for Richard Avedon’s Montauk estate, but it’s less a studio and more, well, the aforementioned way of life. You can partake in that way of life too, if only for a few months. The property rents for the summer for a cool half million. A reminder that Avedon was more successful than the rest of us.

It’s not focused on his studio, but this article about Avedon’s Upper East Side apartment provides a more detailed look into the photographer’s psyche than any studio bts might. Listed for sale earlier this year, Avedon’s apartment was filled with photographs (his own, mostly) and artworks, as well as plentiful books and oddities. It seems we generational photographic talents do have an affinity for odd and interesting objets d’art.

I wrote about Annie Leibovitz a couple weeks ago, and while she has a long and well documented history with New York real estate, I couldn’t find any evidence of her current studio location. She is, however, selling her Central Park West duplex. Listed for $8.6 million, it’s a significant discount off the $11.3 million she paid nearly a decade ago.

Since I’ve gone full Zillow here, why not have a look at Joel Meyerowitz’s Upper West Side apartment. It was a bit of a stretch, he concedes, as the rent was $190 per month back in 1965, but it’s since gone condo and now he’s an owner. The converted dining room houses his extensive archive of negatives and chromes, while the remainder of the space is beautifully functional for the quintessential New York photographer and his wife.

For our friends across the pond, there’s a beautiful rental studio available in London (with a second location in Ibiza if you’d care to shoot while on holiday). Loft Studio is a gorgeous mix of old and new that makes for one of my personal favorite aesthetic juxtapositions, particularly when it comes to photography studios. Yes, this is the one. I’ll take it.

No, wait. Maybe something a little closer to home.

I’m apoplectic with envy every time I drive by, but just 20 minutes from where I sit out here in flyover country the amazing and talented food photographer Jenn Silverberg has built her own dream studio, and it’s the kind of place any photographer would love to live and work.

In an effort to remember that studios don’t make the photographer, but the other way around, let’s end with this. Take a look at this portable studio. Portrait phenom Joey L turned a pop-up tent into a beautiful shooting space, which he carted around Ethiopia for more than a decade making stunning portraits in the simplest studio imaginable. While it’s fun to dream about the stunning spaces, let’s keep our heads on straight. It’s the photographer who makes the work, not the space.

To learn more about Jay Maisel and his quintessential dream studio, check out this film from photographer and former protege Stephen Wilkes. It’s an homage not only to the supremely unique space, but also to the one-of-a-kind creative spirit who turned it into a work of art—and a way of life.

This was a very enjoyable piece Bill. Most of my colleagues, and myself, out here in the NW, all had studios (shared) and it seemed necessary 20 years ago. But the combination of many more photographers and skyrocketing commercial rates over the last bunch of years, has led few people having shooting spaces. And there are fewer rentals now as well and that has led me to pass on a couple assignments.

Short of building my own studio, Owning an old firehouse and converting the truck bays into the studio has always seemed an ideal to me. They are solidly constructed with good utilities, and easy access. The hat trick for me consists of coming up with the money, finding one with good natural light, and finding a good compadre to share it with.