If we have learned anything from Frank Herbert’s Dune saga, it’s that fear is the mind-killer. In the context of that story, the sentiment is about overcoming acute, physical fear. But I like to interpret it as broader guidance for living: on the importance of overcoming all the million little fears that prevent someone from reaching their full potential. This might be fear of rejection, fear of failure, fear of not being able to do something well, fear of the unknown. All of these fears and more, at least in my own experience, never seem especially prominent but they are surely ever-present. They have immense consequence in my own artistic pursuits. And, clearly, I’m not alone.

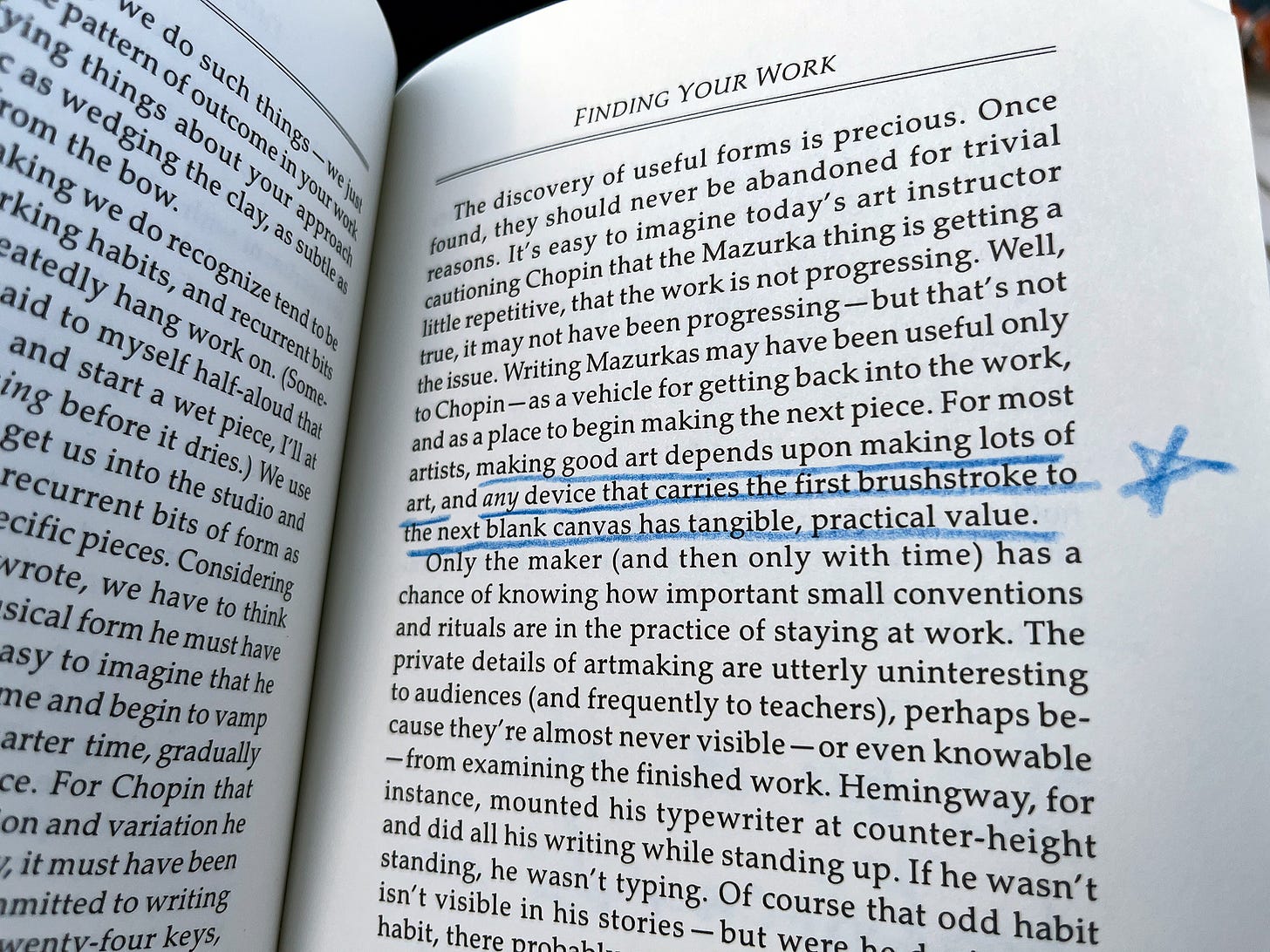

There’s a widely touted book from 1993 called Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking. I’m not sure when I first gathered it was considered one of the greats in the realm of philosophy of artmaking up there with The Artist’s Way and sharing much the same purpose of helping artists overcome the mental hurdles that prevent us from dedicating ourselves to pursuits that are, as the authors of Art & Fear put it bluntly, “doing something no one much cares whether you do.”

Having read it on the beach this week, I now understand why it is so well regarded. Authors David Bayles and Ted Orland have compiled an inspirational treatise on artmaking. It’s self-help, frankly, on the philosophy of not just why one might be interested in making art, but the motivations that help them go about doing it as well.

I found the first half of the book especially inspiring. It is a treatise in learning that we’re not special, and why that’s a good thing.

It turns out many of us make the same excuses. We are not special in that every fear and worry that’s kept us from starting (or finishing) a given project, is the same worry that all (or at least most) artists have shared. When art was sponsored by the church, or made primarily as an act of godly devotion, artists had an easier time finding motivation and clarity about why they do what they do. But for 200 years artmaking has trended broadly toward a more solitary, self-motivated pursuit. As the authors write, “making the work you make means finding nourishment within the work itself.”

“Even talent is rarely distinguishable, over the long run,

from perseverance and hard work."

If your mind’s not right, that sounds like a lot of hooey, I know. But this strikes me as one of those IYKYK situations. The book might be classified as self help, but I found it fairly grounded and practical. Not practical like “first apply gesso to the canvas” but practical in the sense that there’s immense power in learning that your most personal, deep-seated doubts and fears are widely shared. Misery loves company, I guess.

I don’t think of myself as especially fearful, or even much of a negative self-talker. But Art & Fear helped me realize all of the ways I sabotage my process. And so the authors set about systematically disarming every treacherous one.

A pleasant surprise for photographers is the authors’ photo-centric background. Many of the book’s examples reference great photographers (Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Weegee) and while it’s largely immaterial which great artists are referenced, it serves as a helpful reminder for those of us specifically wielding a camera in the process of making art.

Art & Fear is also especially useful as a counterpoint to much of the photography discussion in 2025 (the whole “does equipment matter” hot take bandied about by the world’s smoothest brains, myself included). Philosophy is harder to sell than lenses, so we get more content about lenses. But ideas are so much more interesting than equipment and technique, which should theoretically be in service of those ideas — not an end in and of themselves. These themes are exceptionally relevant to a modern audience of photographers, whether we like it or not.

“We do not long remember those artists who followed the rules more diligently than anyone else,” the authors write. “We remember those who made the art from which the ‘rules” inevitably follow… To the viewer, who has little emotional investment in how the work gets done, art made primarily to display technical virtuosity is often beautiful, striking, elegant… and vacant. To the artist, who has an emotional investment in everything, it’s more a question of which direction to reach. Compared to other challenges, the ultimate shortcoming of technical problems is not that they’re hard, but that they’re easy.”

“Art that deals with ideas, is more interesting than art that deals with technique.”

The artist's job is to make art. Don’t overthink it, don’t perfect the idea before you get started, just do it. The more you make, the better you’ll get. And the better it will get. I believe this to be true, and it’s the foundation upon which this book is built.

In my own work, I find it incredibly helpful to dispel the myth that art is made by geniuses who don’t suffer self doubt the way mere mortals do. The authors counter this within the first few pages, explaining that virtually all artists doubt themselves and their work. The work is just that, work, and it requires no pre-ordainment to commence.

“The conventional wisdom is that while ‘craft’ can be taught,” they write, “‘art’ remains a magical gift bestowed only by the gods. Not so. In large measure becoming an artist consists of learning to accept yourself, which makes your work personal, and in following your own voice, which makes your work distinctive.”

The only thing you can be is you. So be you to the fullest extent permissible by law.

You’re gonna make a lot of bad art. Instead of seeing it as reason to stop, the authors argue it’s just part of the process. Get the bad work out so you can get on with the good.

“The function of the overwhelming majority of your artwork is simply to teach you how to make the small fraction of your artwork that soars.”

Don’t sweat it, they say. Just get to work.

“It’s easy to imagine that real artists know what they’re doing, and that they — unlike you — are entitled to feel good about themselves and their art. Fear that you are not a real artist causes you to undervalue your work… After all, you know better than anyone else the accidental nature of much that appears in your art.”

This book is permission: to get started, to be yourself, to not worry about how or what or anything external, anything on the viewer’s end. This book suggests that the primary thing an artist needs to concern themselves with is doing.

“To the critic, art is a noun…” Bayles and Orland write. “To the artist, art is a verb.”

Understandably, some readers might find the book’s motivational tone flat. This isn’t practical advice in the “how to” sense. It’s right there in the title: It’s about fear, and overcoming those that hold us back from making art. If you’re in a place where this inspiration sounds enticing, I can’t imagine a better pep talk.

“Art work is ordinary work, but it takes courage to embrace that work, and wisdom to mediate the interplay of art and fear.”

Thanks the thoughts; will pick up the book for sure. Also can relate to your notion of not being "especially fearful, or even much of a negative self-talker." I feel that way too; it's not fear of failure that stops me, it's just figuring out how, exactly, to start, given the many many options sometimes...

Love that book. Great review. 4.8 stars.